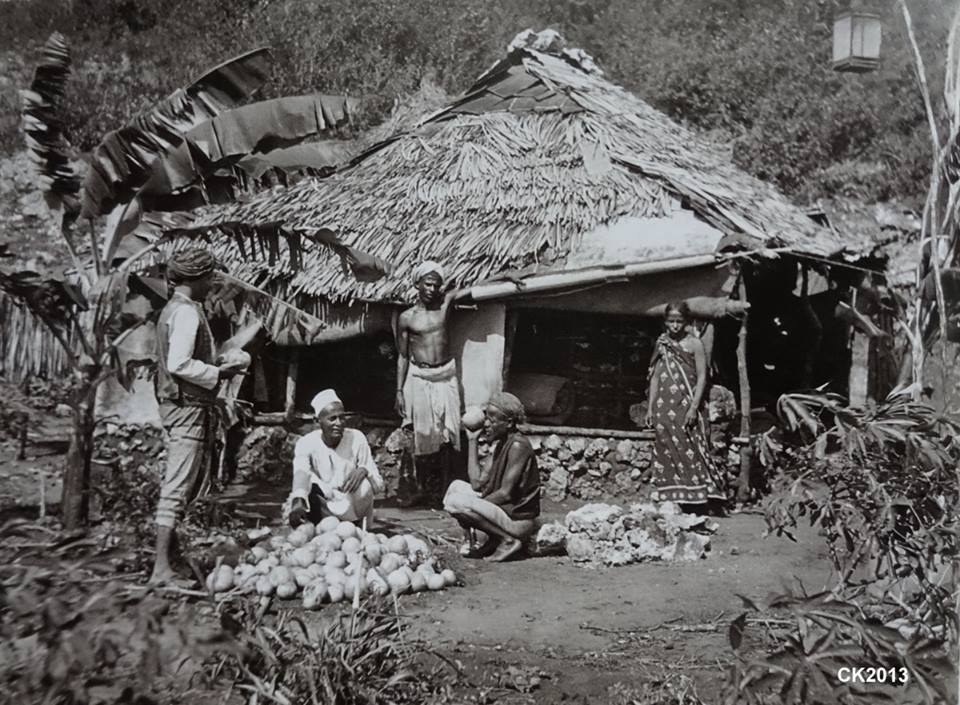

A witchdoctor (centre) and his two apprentices, circa 1958

A fine yet all but impenetrable veil separated Mombasa’s sunny exterior from its darker dimension. Impenetrable, that is, to club-going commonsensical colonials like my parents whose spiritual needs, such as they were, found satisfaction in the churches they had built at either end of Fort Jesus Road; the catholic church almost in the centre of the town as befitted its greater age, the protestant church more discreetly tucked beneath trees and closer to the British enclave of banks and government.

These churches made it quite clear to everyone – Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, those animist Africans who remained as yet unconvinced about Jesus – that clean and godly Christianity was one of the benefits that came from European rule, along with law, order, good government and decent drains. Furthermore, it meant an end to witchcraft and superstition and all that mumbo-jumbo associated with primitive cultures that knew no better. So there were to be no more were spirits inhabiting the bodies of wild beasts; no more jinni in charge of special places, and witchdoctors were either ridiculed or sent to jail. Of course, it was okay to believe in angels and that Satan was still a force for evil in the world and that a man invested with sacred power could change water into wine. But the only ghost sanctioned by the ruling civilization was the Holy Ghost.

Yet beyond the veil Africans and small white children knew differently. We understood that ghosts and unquiet spirits haunted old buildings and certain places around the island. We shuddered at the thought of leopard and hyena lurking in the forests that were no true animals but men, undead, in animal form. We believed firmly that Fort Jesus was haunted by the ghosts of Portuguese who had died there and that under every baobab tree was the body of a slain Arab.

The people of the coast, though mostly Muslim by profession, were deeply superstitious and believed in many things not found in the Koran. In coral caves along the coast you would often find little bundles of sticks with coloured strips of cotton tied to them, like miniature flags. These might or might not be accompanied by carefully laid out oddments – feathers, small stones, shells, driftwood. We children knew that these were placed there by witchdoctors; knew also to leave them alone or we might find ourselves laid under a dark and probably fatal spell. Eagerly we exchanged rumours about children who HAD interfered with these strange artefacts, and who had died awful deaths or simply disappeared. Africans had great dread of these caves and would never go in there; it was marufuku – forbidden – they warned us, and also ahatari – dangerous.

The coral caves found in headlands north of Mombasa Island were a great playground for we children who made our own sort of magic in their dark depths. At low water there were tiny rock pools full of sealife and we would clamber or crawl over the rough coral to sandy-floored chambers where we would play pirates or castaways, always with an eye for the incoming tide. But if we came upon one which showed evidence of uchawi we retreated at once – the broom-riding witches of our own folklore didn’t worry us much but every Kenya child, black or white, feared African witchcraft.

I knew a boy who once came across one of those little collections of flags and, as ten year old boys will, gleefully broke and scattered them, and brought a few out of the cave with him to show his parents. They were a family newly arrived from England and thus ignorant of such things; however when some African fishermen saw him flourishing his booty they became angry and shouted at him. The parents, of course, were completely bewildered by this reaction but thought little of it until, a few days later, a very smooth young man in a cast-off European suit came to the door and told them in passable English that their son had committed a grave offense and compensation would have to be paid to the local witchdoctor. Otherwise, he said politely, very bad things would happen.

The boy’s father, who had been fighting Germans not long before, was not easily intimidated. He laughed and told the young African to go away or he would call the police. Shortly after this small, strange, sinister artefacts appeared in places around the house and garden. Sinister, that is, to those who recognized the signs of witchery. It didn’t worry the boy’s father but it frightened the memsaab and it terrified the servants, who both left. Nor could any others be found to replace them – nobody would work for a household that had been so obviously cursed.

The story went round our small community like wildfire and we children waited hopefully to see whether the boy, our playmate, died a gruesome death or was turned into some demonic creature. We teased him unmercifully but also kept a strategic distance – we feared contamination by association.

Finally, after a couple of uncomfortable weeks, the boy’s father sought advice from the head of his department, who happened to be MY father. Should he call the police? Was his family in any danger? My father, who believed in nothing beyond the realities of this world, nonetheless counseled him to make compensation. Some might have viewed this as giving in to blackmail but my father, wise in the ways of Africans, knew that a serious offence against local cultural and spiritual sensibilities HAD been committed and that while there was little likelihood of any major revenge the witchdoctor would continue to make trouble and subject the family concerned to an ongoing series of petty annoyances. Certainly they would never be able to employ another servant until the curse was lifted. This advice was taken; a small (in European terms) amount of money was handed over, apologies were made and there the matter ended.

I realize that this story would be more exciting if it had a suitably dramatic ending. What it shows, however, is the indirect but still potent power of African witchcraft which could still affect the lives of Europeans through its effects on the people who worked for us.

The people who lived on the coast north of Mombasa blended Islam with their animistic beliefs and and witchcraft – and its practitioners – flourished in those dark forests. According to recent newspaper accounts, it still does.

When I returned briefly to Kenya in 1971 I stayed with some friends who had bought land at Kisauni, just north of the island. This was always one of the coast’s “dark” places, teeming with jinni and troublesome spirits according to local lore. Few Europeans lived there in those days and those who did were the type to be dismissed by my mother as “peculiar” – her favourite word for anyone who didn’t quite fit her notions of middle class social norms. My friends were planning to build a house on their couple of waterfront acres and everything was ready to go when they suddenly ran into a snag – the local witchdoctor had put a curse on the land and would not remove it unless promptly paid. This was not something that could be laughed off because no workmen would set foot on the place as long as it was accursed. In the end, payment was made. It all ended well enough because they lived there for more than 50 years.

Witchdoctors, both male and female, involved themselves in every aspect of life in the villages and shanty towns on and around Mombasa. They were not all bad – some waganga practiced herbalism and spiritual healing and the blessing of family endeavours. Others, however, known in those days as wachawi – a word uttered always with dread – practiced the black arts and were very much feared indeed – shape changers, demon-raisers, death dealers – their auto-suggestive powers were very strong.

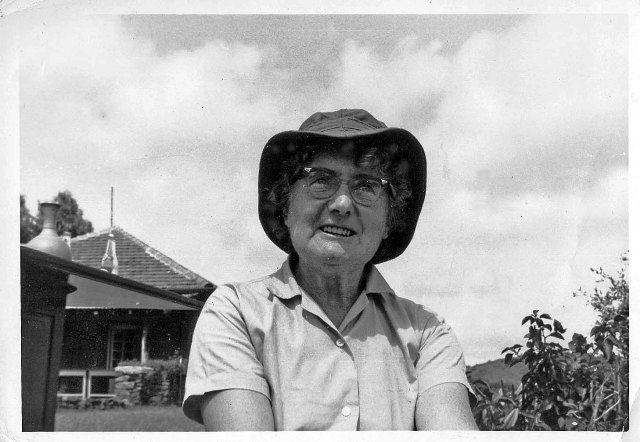

My grandmother was known as a witch to the Kamba people among whom she lived. They called her Memsaab Susu – a word that meant grandmother but could also be synonymous for a witch of the benevolent kind. What we’d call a white witch. She earned this for her knowledge of basic medicines and fondness for herbal remedies. Unlike her family, the Africans whom she dosed with her disgusting nostrums were impressed and grateful and obligingly inclined to recover from whatever was ailing them. They often begged for Milk of Magnesia which they regarded as a cure-all more efficacious than any remedy from one of their own witchdoctors but the medicine which impressed them most – and which they feared most – was Andrews Liver Salts.

My grandmother, a “witch” whose most powerful potion came from a tin of fizzy stomach salts!

My grandmother was in the habit of taking a glass of this stuff every morning and attributed her own excellent health to its properties. To the Wakamba of earlier and less sophisticated years, this foaming drink looked like boiling water and once my grandmother realised this she used it to advantage. If there was trouble in the household or theft among the farm workers my grandmother would subject them to what we called “Trial by Andrews”. All suspects would be given a cup of water into which she would pour a couple of teaspoons of the magical liver salts. Those who were telling the truth could drink safely. Those who were lying, however, would have their mouths badly burned – no liar could evade the curse of Memsaab Susu. Those who were trying to lie did not dare to drink the fizzing water, so strong was their conviction that it would, indeed, burn. “The day will come”, my father used to warn her, “when you’ll try this on one of these chaps who’ve had a bit of education and he’ll drink the water. And then where will you be?” As far as I know, that never happened. My grandmother retained her reputation to the end. I have heard this story of European “smoking water” from others and whether it originated with my grandmother or others coincidentally tried the same scam I don’t know; I only know it worked for her.

I was staying with her during my school holidays when, one evening, there was a ruckus in the kitchen. We rushed out there to find one of the servants cowering in front of a large, very dark-skinned man wielding a knife. Without hesitation my grandmother (who was only just over five feet tall) marched up to him, seized his arm, made him drop the knife and then demanded to know who he was and what was going on. It turned out that the cowering servant had recently purchased a wife who had been promised to the tall stranger, who was determined to claim his own, by force if necessary. My grandmother ordered him off the farm but he hung around the labour lines for a few days, trying to foment trouble and making threats against both the servant and my grandmother.

He was, we learned, a well-known m’kora – spiv – greatly feared by the locals and said to be under the protection of a powerful witchdoctor – a mchawi. “We’ll soon see about that”, snorted my grandmother or words to that effect, and promptly put a spell on him. Her spells consisted of waving a riding crop in the air and reciting English poetry, usually that one that begins ” Sunset and Evening star, and one clear call for me…” which she chose, as she said, for no reason other than she’d always liked it. The watu were enthralled, for Memsaab Susu’s spells were considered more fearful than any local thug. Sure enough, a few days later, my grandmother was told that the stranger had gone to a hut in a nearby village, lain down on the ground, and since refused to move or talk or eat. This went on for a while – I can’t now remember how long but it was during the Easter school holidays so can’t have been more than another week.

I returned to boarding school and learned later that the villagers had come to my grandmother and informed her the man was certainly dying. Sceptical, but a bit worried by now, my grandmother went to see for herself and, sure enough, the big, very dark stranger whom I remembered as being well-muscled and quite frightening in his obvious strength was now lying there shrunken, grey of skin, comatose. My grandmother hastily produced another of her spells and ordered the man to recover. Within a few days he did so and, terrified by this small white woman with her tin of Andrews Liver Salts and riding crop, left the district.

This all occurred up-country but those tribespeople who went to the coast to work, as our Kamba servants did, took their superstitions with them and then had to confront a whole new lot of what my father and his friends called “mumbo jumbo” but we children believed in as firmly as did the servants who helped raise us.

We knew of the devilish spirits that inhabited certain baobab trees and were afraid to go out after dark, even into the garden, for fear of the big, black nyangau – a flesh-eater with certain similarities to the hyena, only scarier. I’ve already mentioned the were creatures that also lurked after dark; leopard and hyena were the most popular choices for those men and women who transformed themselves into animals but just about any creature could be thus inhabited – any creature with teeth and claws that is. I’ve heard of were jackals and even were serval cats but never of a were elephant! These and other horrors had much in common with vampires because their aim was to suck your blood or your entire essence and then inhabit your body.

In the late 1950s there was a sudden fad for “hugabug dolls”. These hideous inflatable black plastic dolls with staring eyes became an object of desire for every little white girl in Mombasa – and probably in Nairobi too. The fact that they were quite unlovely to look at mattered nothing to us, if one girl was seen at school or in town with a hugabug clinging around her arm then the rest of us wanted it too.

When I eventually got mine, from the local toy shop, I went and showed it to the children next door. Their ayah promptly threw up her plump arms and gave a startled hiss. She would not be in the same room as the doll, nor allow it near “her” children. Our own servants were similarly uneasy and the houseboy avoided looking at it when cleaning my bedroom , asking my mother if it could be kept in the wardrobe. This story was repeated in households all over Mombasa, with some servants threatening to leave if the dolls were not removed from the premises. When pushed, they would not say exactly what it was they feared and disliked, but would just mutter that it was “mbaya” and “uovu” and look down at their feet in that way that Africans of that time used to do when the Europeans upon whom they depended were being particularly obtuse.

To be honest, I never really liked my hugabug doll very much. One night, perhaps influenced by our servants’ unease, I woke up and saw it staring at me from its habitual place on the top of a bookcase. Its round eyes with their white outer edge, its red mouth and fat little ever-reaching arms suddenly struck me as sinister. I turned on the light and huddled under my mosquito net, hardly daring to sleep in case it came for me. In the morning, of course, it looked perfectly harmless but I pricked it with a pin, nevertheless, and threw away the deflated carcass. When I unwisely confided this to a boy down the road he told me to watch out at night because the hugabug would return, reinflated, to take its vengeance on me. So I slept with the light on again, that night and many nights thereafter, despite my parents’ exasperated assurances that it was all a lot of nonsense.

As with all such things the hugabug craze died as swiftly as it had arisen but the fear stayed with me for quite a while – and that was many years before Chucky!

Africans could create terror out of almost anything. One of the strangest stories involved the truck that went around pumping out septic cisterns in the villages along the south coast. This “honey wagon” was introduced as part of a move by the local government to improve village sanitation. Somehow, a story was put about that this wagon was in fact a kind of vampire that would suck out the souls of villagers. Witchdoctors were brought in to curse it and to protect the villagers. Attempts were made to block the tracks so that the septic truck couldn’t get into some villages. Stones were thrown at it. People would hide their children and retreat among the coconut palms when the wagon came to do its work and the crew could count on no assistance from local men in playing out the pipe and setting up the pump.

I can’t remember the name they gave this creature but it was something like “tamiami”. Nor can I remember how the matter was resolved, though it obviously was.

Africans, whatever their tribe, did not readily surrender their belief in witchcraft to European influence but under Colonial rule they had learned to keep it to themselves; a dark and sometimes dangerous secret which only came to the attention of White settlers when something overtly dramatic occurred. In which event, the matter would be discussed around the dinner table or in the club; scornfully, perhaps, or with amused condescension, but often with an uneasy sense that “maybe the watu knew a thing or two” that we sophisticated White people had forgotten. One such case – a tragic one – comes to mind, dating from the early 1960s.

It concerned the cook, in the household of one of Mombasa’s wealthier European merchants. The cook was a Taita, as was our own mpishi, and this is why I remember the story so well. It was much discussed in Mombasa at the time, in all the usual places where such things were discussed by the white population, but as our cook Mboji was a friend of the man in the centre of the story, our household was given an unique perspective.

The Taita cook, who lived in the spacious servants quarters behind a grand house in Kizingo Road, had a wife with a very bad temper. Fortunately for him, she lived in their tribal village somewhere around Taveta. Alone at the coast, he did what so many other men in his position did, and took a girlfriend. This girlfriend was said to be a malaya – prostitute – or at least a woman of easy virtue – but this may just have been a malicious rumour. In any case she became pregnant and the cook moved her into his quarters (unbeknown to the Bwana!). Somehow, the wife got to hear of this and came down to the coast in a jealous rage. She found the girlfriend in situ and (according to witnesses) a spectacular cat fight took place. The girlfriend fled – but not before the wife had cursed her unborn child. The baby was, indeed, born dead or else died soon after birth. The (presumably) distraught and vengeful girlfriend then employed a witchdoctor of legendary powers to put a curse on the wife. Now it was the wife’s turn to die. The cook came into his quarters one night and there she was, on the kitanda, eyes open and staring, not a mark on her, no signs of illness and dead as the proverbial doornail.

Our family got all this information from Mboji, who had time off to attend the funeral. Of course, there was an inquest and the whole affair even made the papers. The examining medical officer could find no satisfactory cause of death so it couldn’t be certified as accident, murder or natural causes. Nonetheless the police hauled both the girlfriend and the witchdoctor in for questioning and it turned out that the latter had been in their sights for some time – apparently the cook’s wife was not his first “victim”. They charged him with various nuisance violations but had no chance of getting him on a murder rap – witchcraft, if proved, WAS a banned practice but it didn’t rate as a capital crime. And these were sensitive times – with Independence just around the corner. So the whole matter just fizzled away.

The cook’s employer decided to get rid of all his servants and start afresh for the affair had seriously embarrassed him and caused a lot of nuisance The cook was a very good cook – said to be one of the best in Mombasa in fact – but his philandering ways had proved fatal for some and indeed, as the police’s first suspect, he had spent a fair bit of time in gaol. The rich merchant was unmarried and his household was presided over by his spinster sister – a gentle, deeply religious woman who ran a small Christian youth group in their large house, and used to take me to church on Sundays when I was at primary school. She urged her brother to employ only avowed Christians from then on, so that there would be no more immoral and ungodly fitina. Poor innocent, she had lived many years in Africa but still didn’t understand that even those Africans who embraced Christianity tended regard it as a comfortable addition to, rather than a replacement for, their own centuries-old beliefs.

Uchawi would continue to exert its powers over the people of the coast, even though the new government claimed to be just as keen as the Colonial Government had been to stamp it out. Why, just the other day I read of a couple of cases in Kenya which had come to the attention of the authorities – and the media. These took place in the highly-superstitious, overtly Muslim region north of Mombasa where poverty is endemic and village life has not greatly changed since Independence more than sixty years ago. Though it could have been just about anywhere in outwardly-sophisticated modern Africa where old ways may have been forced underground but don’t easily die.