Teenagers, as those of my generation know, were invented sometime around the mid –to-late 1950s. There weren’t any before then – just children who became adolescents who then made the sudden leap into official adulthood at twenty-one. No matter if you had been out to work since the age of fourteen and had a driver’s licence– you weren’t taken seriously as a fully-fledged member of human society until you were given the key of the parental door. Unless, of course, you were silly enough to have got married – as many of us did for the very reason that it gave us adult status.

Teenagers were invented in America, like just about anything else back then, and the idea soon crossed the Atlantic to hybridise into sub-cults like Teddy Boys and, a bit later, Mods and Rockers. Young men slicked back their hair into duck tails and grew sideburns. They dressed in drainpipe trousers and draped jackets. Girls bound their hair into pony tails or combed it up into “beehives. THEY went forth either in a frou-frou of full skirt and starched petticoat, or else pencil-tight skirts or pedal-pushers, feet shod in bobby socks and flats or stiletto heels. Rock and roll ruled the airwaves, prime time TV programs were dedicated to “pop” music, records went vinyl and society suddenly discovered that the youth market was a goldmine because – hey! – for the first time in history kids had money to spend!

All this reached Kenya rather late. When Elvis was warning people to keep off his blue suede shoes most white Kenyans between the ages of, say, 13 and 18, were still schoolchildren following the same pursuits that their parents had followed before them. Even if we’d left school our leisure time was still influenced by the activities of the previous generation and we inhabited that uncomfortable no-man’s land between childhood and adulthood, where little account was taken of our adolescent desires.

Not so bad if you lived in the country because there you had horses and could shoot things or go camping or tear around the bush tracks, unlicensed, in a Landrover. For townies, however, the school holidays and weekends could be dreadfully dull. You couldn’t be forever playing tennis or Monopoly. Those lucky enough to live at the coast had, at least, the beach for amusement. But even that offered little amusement when evening fell and you were too old to go to bed early but too young to go dancing at the Sports Club, or to the cinema without a chaperone.

However, by the time Elvis had changed his tune and was out of the army singing It’s Now or Never things in Kenya had changed too and the cult of teenagehood was well and truly established. Suddenly those of us born during or at the end of World War 11 found ourselves with a collective identity and parents with the time, money (comparatively speaking) and social awareness to indulge us. In Mombasa this new recognition manifested itself mainly in the introduction of special “teenage dances” every Wednesday evening during the school holidays.

These were run by the East African Women’s League which was very brave of that ultra-respectable organisation because supervising a bunch of youngsters with their hormones running wild and hell-bent on making whoopee is not for the faint-hearted. As we all know, the EAWL was formed of doughty gels up to anything from scaring off a rampaging lion to executing the most exquisite of embroidery stitches so those who volunteered to supervise the teenage dances were obviously made of stern stuff. They had to be youthful enough, or at least youthfully aware enough, to let us have plenty of fun while at the same time able to command sufficient respect to prevent excessive behaviour such as drinking, fighting or having sex behind the cricket screen. As far as the first two were concerned, they were generally successful.

The dances were held in the Railway Club. This was centrally located at Mbaraki and its membership was tolerant enough to allow we rock and rolling youngsters to take over the joint for one night a week, eight weeks a year. Such a thing would have been inconceivable at the Mombasa Club and even the popular Sports Club was obviously not prepared to yield up its wonderful sprung dance floor to the juvenile brigade. From memory we paid a small fee though this could hardly have covered the cost of the excellent and youthful live band that could play everything from early jive to the latest pop tunes to foxtrots and sambas. In truth we were a lucky lot – we Mombasa kids of the late fifties and sixties, to have had all this laid on for our delight.

Yet to this day I still shudder at the memory of my first teenage dance. I was only thirteen at the time and still something of a tomboy. My only experience of dancing, apart from ballet, was the obligatory ballroom lessons given weekly at our Nairobi school and some clumsy attempts to practice my steps at the Saturday night hops held in our boarding house. There, of course, girls danced with girls and we younger oiks were barely tolerated on the common-room dance floor by our seniors.

Timid is hardly the word to describe my feelings at my first public dance. Terrified would be more like it. I’d only gone there at the command of my mother, who was one of the regular chaperones at the teenage dances and, indeed, one of the most enthusiastic proponents of the whole idea. She was also among the most popular with the kids, being herself quite young, pretty, fashionably-dressed and easy-going of temperament. This latter quality meant that she was inclined to spend more time sipping cocktails and gossiping with the other chaperones, or any stray member of The Railway Club foolish enough to risk the bar on teenage dance nights, than keeping an eye on her charges.

In general, my mother was not a natural habituee of the Railway Club and was usually to be found at the Mombasa Club or, in younger days, at The Sports Club. But she was an affable soul who could chat as easily with engine drivers’ wives as she could with the old codgers at the “Chini” Club across town. “Oh good, your Mum’s on duty”, the other kids used to say to me, knowing that our activities would not be overlooked too scrupulously and the smoochy “lights-out” period that ended every dance could be extended.

Not all the EAWL women were so sympathetic. On one occasion a certain prominent committee member with a spurious double-barrelled name and an even more spurious posh accent (cruelly mimicked by my mamma to amuse friends and family!) opened the night’s events by pleading with us to “why not enjoy yourselves gels and boys with some naice quicksteps and waltzes instead of all that horrible rock and roll” and instructing the band to play her kind of music. Some of the older boys – men, really – objected strenuously and threatened to go home. The whole future of the teenage dances hung in the balance and Mrs Double-Barrel reluctantly yielded – but spent the whole night patrolling the dance floor like a sergeant-major and forcibly separating any couples who got too close during “lights out”. “Silly bitch”, said my mother to my father, in my hearing, voicing a sentiment which no teenager of my day would have dared say aloud. And so, thanks to my mother and the other younger and more “with-it” supervisors, the dances continued – a highlight of every school holiday.

Still, at that first dance, I was far from considering it a highlight and was furious with my mother for making me go. In truth, I was still too young. Only one or two of my friends were there, under similar duress, and similarly dressed in childish clothes. I wore, I remember with embarrassment, a white broderie-anglaise blouse buttoned to the throat and a flared yellow skirt with white ricrac round the hem. No starched petticoat to fill it out; it just hung in dull, chaste folds from the waistband without even a belt to make it look a bit more grown-up. Worse still, I wore white socks! True, this was the age of the bobby soxer, but that particular dress code had never really caught on in Kenya and all the older girls wore stiletto heels. I don’t remember the shoes I wore and only hope they weren’t those Bata sandals with little bits cut out of the toes! Or were they Clarkes?

When you walked into the Railway Club there were the lavatories on the right and then the bar area and the main club room on the left, which was where we danced. Outside was a patio overlooking the sports field. Around the room, wooden chairs were arranged. Here, on these wooden chairs, sat the novice boys and girls. The shy, the plain, the fat, the skinny, the spotty, the non-dancers. The in-crowd; those Godlike beings who were older and better dressed and more popular than the rest sat in groups at the clubhouse chairs and tables. When each dance started I, and the other little girls of my acquaintance (and there were painfully few of us) sat stiffly on our chairs, eyes cast mainly upon our shoes but straying occasionally upwards to watch, with envy, those older teenagers flinging themselves so confidently around the dance floor.

We took an occasional peep, too, at the boys of our own age or slightly older who sat with equal stiffness across the rooms. They, too, had been parentally coerced into attending the dances, usually with the well-meaning idea that this would improve all our social skills. Which, eventually, it did. Though perhaps not always in the way that was intended! The European community of Mombasa being small, and the community of the young smaller still, we knew most of those boys. Like us, they were finding their feet for the first time in the often brutal world of boarding school, or else the difficult transition from boarding prep school to high school, and were gawky and awkward with neatly parted brylcreamed hair and less adept than we were at hiding their spots. And, despite the fact that they had been playmates just a short time before, racing around with us on bikes and exploring the caves on the seafront and daring each other to dive off the higher boards at The Florida pool, in this newly slicked-out guise and in this strange venue they had become strangers to us.

Yet it was only from this disappointing pool that we younger girls could draw our dancing partners. None of the desirable older boys would be caught dead jitterbugging with an adolescent wearing white socks! Occasionally one of the EAWL chaperones would go up to one of the young, chairbound boys and cajole them into inviting one of the young, chairbound girls to dance. Across the floor he would come, shuffle-footed, tied of tongue, eyes darting everywhere but at the target. And we girls would sit there, smiling and chatting frantically to each other to show we were having a good time, pretending the boys didn’t exist and at the same time whispering inside ourselves “Pick me! Pick me!” I remember, still with some pain, seeing some spotty youth whom I remembered from Mombasa Primary heading my way and feeling both disgusted and grateful at the same time, and nervously readying myself to accept even though I couldn’t really dance and knew I would make dreadful fools of us both – and then he asked the girl next to me! Oh, the mortification! This was my first dance and nobody asked me at all and when I got home my mother – who had not been on duty that night, wanted to know if I’d had a good time!

This painful experience was repeated a few times though I was, when at home with my girlfriends and the record player, and back at the Saturday night boarding school hops, gradually learning to dance. And, too, boys sometimes asked me on to the floor, though only when prompted by the well-meaning chaperones. Mostly, though, myself and other plain little girls, and all the plain little boys who would so much rather have been at home reading Beano and Dan Dare, sat there admiring the older dancers – and learned with our eyes. Oh I can see them now as clearly as ever, those beautiful girls and boys of sixteen and seventeen. Mombasa had, I now realise, a surprising number of good-looking girls in my day who would have held their own in any beauty contest anywhere and during the fifties and sixties many of them strutted their stuff at the teenage dances. Most beautiful of them all were the Italian girls and their faces are before me as I write – vivacious Gloria who danced so splendidly, elegant Marilva, and Marialena who was as lushly gorgeous as any movie star. How I envied their flowing hair, their stylish clothes, their earrings. And the boys who partnered them were all magnificent dancers and handsome in the dark Italian way. They were the stars of the teenage dances and seemed impossibly up there beyond the reach of we ordinary mortals.

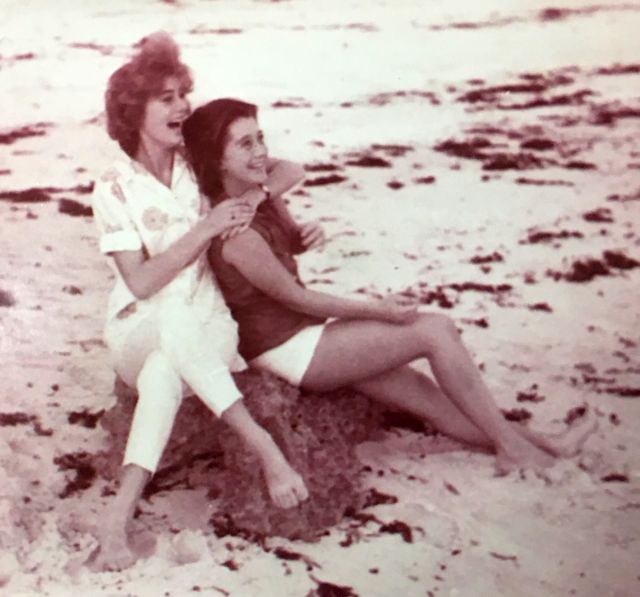

Top: Winning a rock and roll fancy dress prize, age 14, with my friends Marilyn and Lesley. (Not at the Railway Club). Bottom left: An afternoon on the beach was often the precursor to a night of rock and roll at the Railway Club; at left, myself aged 15 on the Mombasa Swimming Club beach and, bottom right, on Nyali Beach, at 16, with my best friend Valerie, another enthusiastic participant in the Wednesday night holiday teenage dances. Valerie and I still live just an hour apart.

And then, suddenly, the longed-for transformation took place and within a year or so – so swiftly do things change for teenagers and yet how long does that time of transition seem to last – I was one of the “in-crowd”. A cinderella, magicked from the ashes of pubity who no longer slunk into the dance hall wretched with shyness but instead flew in blithely with the rest of the flock, greeting friends, giggling and squealing, tossing hair, eyeing the boys with a sharp look out for the boy, rushing to the Ladies to put on forbidden make-up and earrings nicked from my mother’s jewellery box. I used to “borrow” her high heeled shoes, too.

And dance! All of a sudden I was the dancing queen – out on that floor with partners competing for my hand and winning competitions. Even some of those desirable older boys were no longer too proud to give me a whirl now and again, even if they returned to their steady partners when the lights were turned down for the last dance. This last dance was a ritual – when the band stopped playing rock and roll and turned to the slow, romantic ballads of our parents’ era and darkness descended on the dance floor then couples would move in to a clinch. For steady daters this was a chance to indulge in some officially sanctified necking. For unattached boys bold or lucky enough to have grabbed the girl of their dreams before the lights went out it was a chance to declare their interest with a bit of cheek-to-cheek and perhaps a daring kiss and, if not discouraged, a bit of frottage. For girls lucky enough to have been chosen by the boy it was the very acme of teenage romance – a kiss and a hug to boast about to your friends the next day. Many romances did, indeed, begin on that dance floor. Some were consummated down behind the cricket screen or in the car on the way home. Others led, in time, to marriage. For all of us back then it was an important right of passage; the only opportunity we had to make acquaintance with the opposite sex and embark on that best of all games, the Mating Game.

It never occurred to us that we were extraordinarily fortunate to be doing what young people all over the world were doing – but in a far, far more special place than most. Mombasa, when you think of it, was so perfectly made for romance. The palm trees, the white beaches and turquoise sea, the constant warmth that meant we could dress lightly and prettily all year round, our bodies bared to the gilding sun. We were all of us the children of privilege, free of responsibility, cossetted by servants, well-nourished on post-war abundance. Not as privileged, perhaps, as those Bright Young Things who emerged from the previous war and were glamourised by novelists. But privileged, nonetheless, compared to those living in a Europe still throwing off the last shadows of war or a United States where youth rebellion was beginning to take on a darker cast and rising crime was ever ready to prey on teenage vulnerability Whereas there in our small and lovely town on a small and lovely island in a country also poised for drastic social and political change we kids rocked innocently on, as far around the clock as we could get.

When the lights went on again my friends and I would open our blissfully-closed eyes, withdraw reluctantly from our partners and make another mad dash for the Ladies where we would strip off our make-up and flashy Woolworths jewellery before our fathers (or mothers) arrived to pick us up. Until I was sixteen and had a steady boyfriend with a car (and was allowed to wear make-up, though not to pierce my ears) I was always collected by my father. Or the parent of an approved friend. In vain I pleaded that this would blight my social life forever; my father was adamant. I considered this a form of child abuse – it never occurred to me that my father, tired from a day at the office and perhaps a difficult meeting or two, and a post-work game of tennis or golf, was making a considerable sacrifice in taking out the car and going to pick up his sullen, ungrateful daughter at 11 o’clock at night. That his strictness was, in fact, an act of love. The Railway Club carpark would be full of such parents, smoking and gossiping until their offspring emerged, hot and sweating and dazed with frustrated lust, or else still full of high spirits. It occurs to me now how very tactful most of them were, not to intrude on our teenage world by arriving early and hanging around watching us from the edge of the dance floor. Perhaps they were afraid of what they might see!

Today’s young – my grandchildren for example – would consider those long ago dances and adolescent grope-fests tame affairs indeed. They would laugh at our long drawn-out mating rituals where dancing was such an integral a part. And at our notions of “going steady” as a natural precursor to marriage, which at least, for some of us, made sex permissible. After an awful lot of heavy breathing and groping in the back seat of cars or on beach blankets. Yet I remember them with great affection and I’m sure others do also. They were, too, remarkably free of trouble considering the amount of testosterone on display. In fact in my time I remember only one unpleasant incident and when I recall it now it tells me a lot about our social attitudes back then.

The teenage dances at the Railway Club in my day were organised on behalf of those young people still at school and though teenagers who had already left school were not excluded they tended to regard the dances as rather too juvenile. They, after all, were free to join the adults on the dance floor at Nyali Beach Hotel or other such places and, being in the workforce, had money to spend.

In any case, the EAWL, with the support of the Railway Club, did vet the dances carefully to ensure that “undesirables” were excluded. I have written elsewhere in this collection about the subtleties of social discrimination in Kenya society; suffice it to say here that “undesirables” meant, for the most part, those boys and young men who did not go to one of the definitively “good” and “white” schools: The Prince of Wales, Duke of York and St Mary’s. Or perhaps an English public/grammar school and home to Kenya for the hols.

There were, in the Mombasa of that time, young men who did not quite fit this profile. They tended to wear leather jackets, ride motorbikes or hotted-up cars and be of mixed race or else identifiably working-class. One such lot had even formed themselves into a gang – the nearest thing we had in Kenya to bikies. They had a certain lure for we girls – some of us at least – who tended to identify them with Marlon Brando or James Dean. OUR boyfriends were cricketers or rugger buggers; decent, predictable and a bit unexciting. We knew we’d probably end up marrying one of them but still our adolescent dreams yearned secretly for The Leader of the Pack – deliciously dangerous, possibly doomed and definitely forbidden! It was this type of youth that the good ladies of the EAWL, acting in loco parentis, scrupulously attempted to ban from the innocently middle-class teenage dances. Of course, the ban didn’t always work. The young men sneaked in – or sometimes boldly strode – through the back way and dared each other to take to the dance floor, with one of “us” as partners. They were invariably very good dancers.

A friend of mine was being pursued by one of the “undesirables”, known to us as Mike. He was shortish, wiry, dark-hair slicked back into a DA and yes – despite the cloying heat of the coast would wear a leather jacket when riding his motor scooter. He had been to no school that we recognised, his parentage was obscure (i.e. not known to OUR parents) as was his nationality – some said he was Maltese, others Slavic but I now realise his surname was Armenian in origin. Mike had a cocky manner that would have irritated any protective father but went down well with young girls. And one night he walked nonchalantly into the Railway Club and asked my friend to dance. Worse, he kept hold of her hand when the dance was over and then led her outside where they sat with his arm possessively round her shoulders.

Going outside with a boy was generally a declaration of sorts – an indication of romantic interest and, often, a prelude to sneaking off behind the cricket screen! Mike danced – rather flamboyantly for he was lithe and very good and could throw a similarly skilful partner over his shoulder – with others of us that night, though mainly with my friend, and very closely, too. I don’t know exactly what happened – whether he was asked by one of the chaperones to leave or whether one of “our” boys took objection to him – but a fight broke out. I remember thinking it was rather thrilling – like West Side Story! A rumble! Mike wasn’t alone, he had a couple of mates with him and though they had not danced but hung around the edge of the dance floor looking ill-at-ease they weren’t the sort of boys to back off from a friend in trouble.

The EAWL ladies clucked like hens and, as far as I remember, somebody in authority from the Railway Club waded in and separated the fighters and threatened to call the police. Mike and his mates left. I got a stern lecture afterwards from my father about not encouraging the attentions of such youths and what he would do to me if I was ever seen in their company! Mike’s brief fling with my friend ended when she left school shortly afterwards and went to study in UK. I met him again, some years later, in Zambia. We were both married by then, with children, and he had some sort of dull, respectable job. The DA and the leather jacket had gone, along with the Vespa, but the cockiness was still there. I asked him what exactly had happened at that long ago dance and it was obvious the memory still irked. “Those dances were kids’ stuff,” he said, with something of the old, carefully cultivated sneer. “I only went there for a dare and because I knew it would upset those snobby old biddies”.

Kids’ stuff perhaps, but how quickly kids grow up. Soon enough – though we are only talking a matter of three or so years here – the lovely Italian girls and their beaux had danced themselves into maturity, even matrimony, and their places were taken by myself and the friends of my age, and our boyfriends. Now we were the much-envied older crowd, confident in our dancing and sexual allure, and another lot of scared young girls and boys were inhabiting the chairs around the dance floor, being cajoled into getting up to dance or fearfully hoping – and dreading – to be asked.

The last time I went to one of the Railway Club Teenage Dances I went there not to rock and roll but to show off my engagement ring, and my fiancée. Absurdly young, I had nonetheless achieved a social triumph in the eyes of my peers (if not my parents!) by managing to snare a man six years older than my still-teenaged self, who had a respectable job and a car. No more teenage dances for me! Nor for anyone, because not long after that, when Independence came, the dances were discontinued. The young white bwanas and memsaabs – most of them – left for new lives in new places and graduated to nightclub dance floors around the world; to Twisting the night away and, in time, Disco.

I am an old woman now and as I write this my mind goes back to those hot, sticky nights on that tropical island with the starched skirts whirling and the high heels deftly tapping and the pretty girls and the slim young men and all that energy that would have rocked us around the clock if we’d been allowed – and I hope, oh I hope, that the young folk of Mombasa are still dancing today.