I have travelled the world’s coastlines and now live in a country of many fine beaches but I have never yet seen beaches more perfect than the Kenya beaches of my childhood.

Of course, as with all my African reminiscences, my mind is harking back to a time as well as a place. A time when I, a child of privilege, had as my backyard a couple of hundred kilometres of exquisite white sand and turquoise sea and sighing coconut palms.

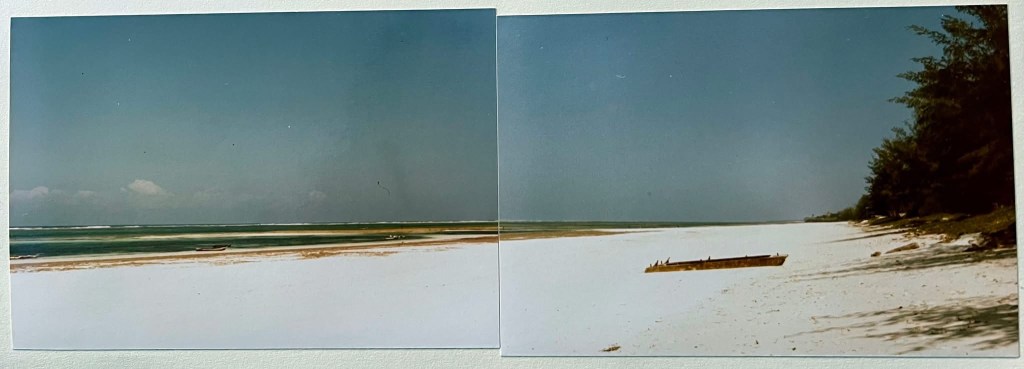

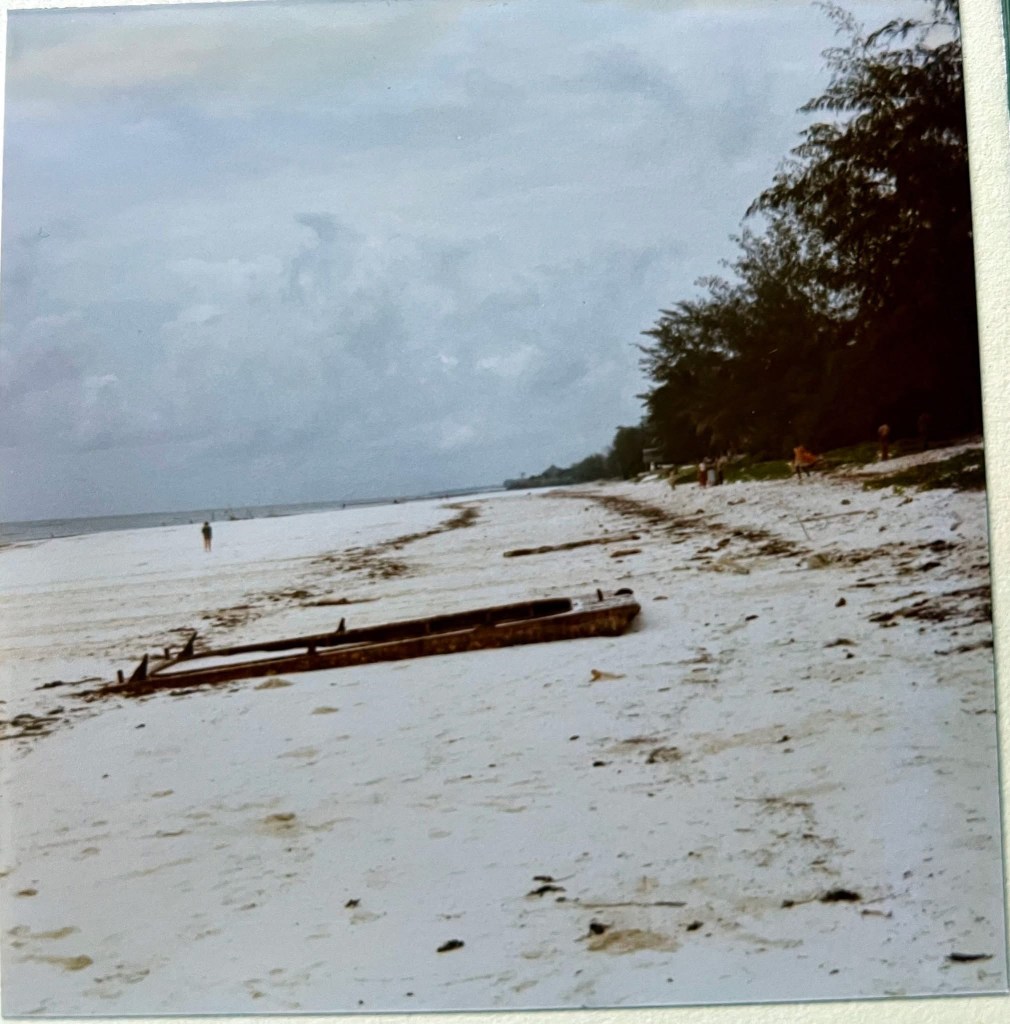

The varied faces of a typical Kenya beach. Photos by Thomas Ackenhausen.

And these beaches were all but deserted, except for a few local fishermen who earned their meagre living there. And, on weekends, the “white” community for whom going to the beach on Sunday – or even Saturday – and any day during the school holidays – was a type of holy ritual. It was our main form of recreation, our temple of pleasure. And we knew we had something special that could be found in few other places on earth.

Of course there are plenty of beaches around the world with sand white as snow, fringed with palms and overlooking an ocean sparkling in more shades of blue than you ever see in a painter’s palette. But what made the Kenya coastline so special was the reef, located a mile or so offshore and stretching from near Malindi in the north to about Shimoni in the south, which protected the beaches from rough seas, big waves and sharks. When the tide was full, we could swim in safety and enjoy a bit of body surfing or just jumping up and down in the modest waves. And when the tide was out….

…Aaahhhh…when the tide was OUT! Then indeed we had a playground full of fascination. For the seascape from shore to reef was a mosaic of coral outcrops and gleaming pools, some shallow, some deep enough to lie in or even swim around a bit. The white sand at the bottom of these pools was pristine apart from a small scattering of shells and little, darting, bright-hued fish. And the occasional crab scuttling from one outcrop to another. There was so much of interest in these pools and in the coral. And a few dangers, too. Moray eels lurked in crevices, sharp of tooth and aggressive to small, inquisitive hands. Sea urchins clung to the hard surface, spines dark and painful if you stepped on them. Which we did, and suffered the consequences when the punctures became infected, as they often did. But apart from these minor irritations, a child – or an adult – could spend the long hours of low tide mucking about in the pools or walking out to the reef or looking for shells which – back in the fifties and early sixties – could still be found there.

The fishermen in their frail-looking outrigger canoes would seek out the biggest and most commercially-valuable shells – the conches and cowries – and sell them to traders or to white folk on the beach, particularly those on holiday from up-country who would take them home as souvenirs. We locals were more blasé, though there were few European homes in Mombasa back then without a giant conch shell lamp! By the time I was in my teens these large shells had become over-harvested and rarely seen but we could still find leopard cowries and take them home and leave them to stink in the garage or on a veranda ledge until the sea-starved dead “dudus” inside had disintegrated or been eaten by ants.

Few of us children were lucky enough to live right by the beach and of course there were no real beaches on the island, except for Tudor Creek, and we didn’t think much of them! Murky, muddy, full of sharks and – it was rumoured – crocodiles. So we were dependent on our parents to take us there, and for most of us this was a Sunday outing. A picnic would be packed and a groundsheet or blanket to sit upon. Sandwiches and perhaps quiche, which we called egg and bacon pie, and fruit. Possibly cake. Never chocolate because it melted in the tropical heat. We kids didn’t care – all we wanted was to get there and stay there for as long as parental tolerance and comfort would allow.

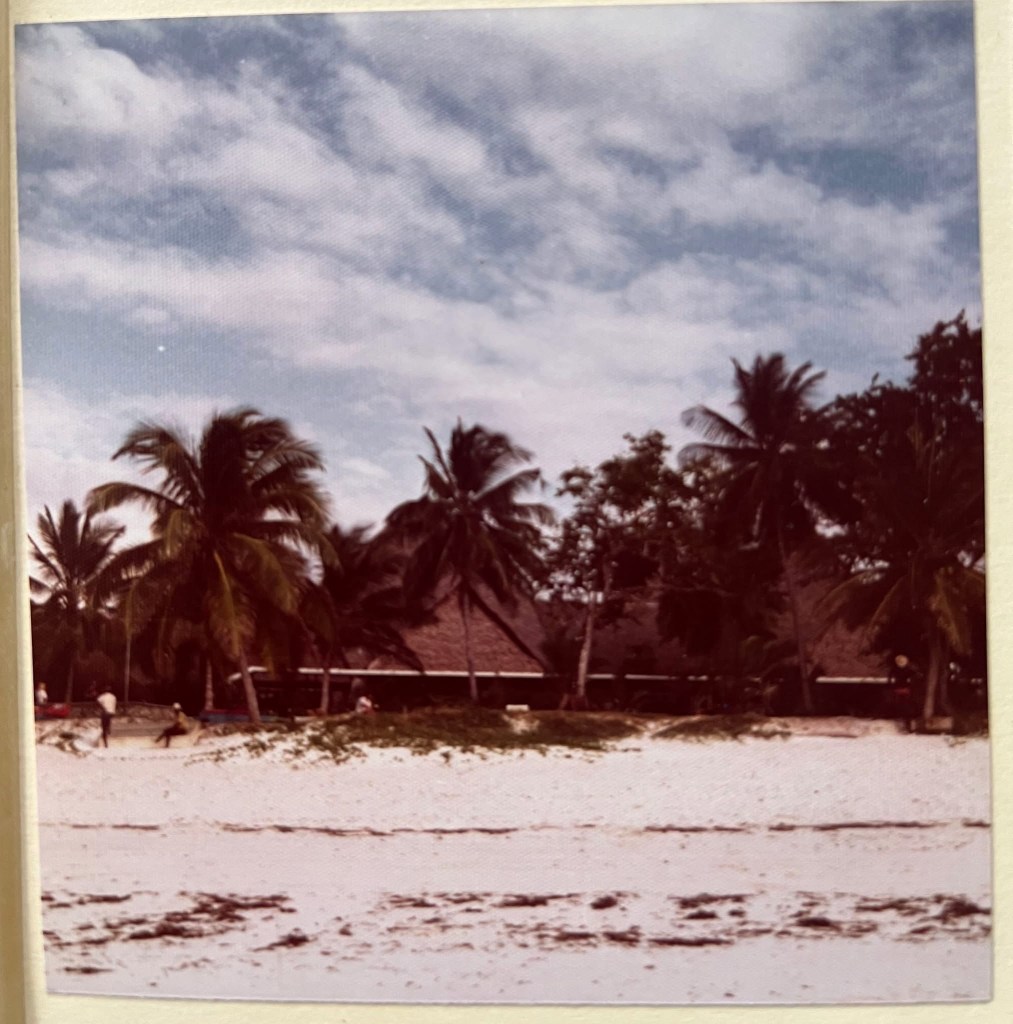

Top: Whitesands Hotel in the 1950s and Bottom: Nyali Beach Hotel about the same time. These were two of the popular beach destinations on the northern beaches, both for up-country holidaymakers and locals looking for a day out.

We were never bored. If the tide was out, we had a thousand pools to play in. If it was in, we swam and played water games. We also built sandcastles. Or drew hopscotch lines. If the grown-ups could be persuaded to play with us there was cricket and rounders, with improvised wickets and bases gathered from the debris beneath the palm trees and casuarinas. The endless imagination of children meant we were never tired of the beach – in the days when reading books, the weekly radio shows and an occasional visit to the cinema were the only forms of entertainment. We were pirates, we were shell seekers, we were castaways building our own palm-thatched shelters. Skinny, sunbrowned, always on the go. And we went for walks, too, both with our parents and alone. It was so safe, back then, on those beaches. You could walk, alone, for miles and in the long distances between the handful of beach entry roads and modest hotels and see only a friendly fisherman, checking his traps.

Fish trap under construction. Photo courtesy of Robin Swift.

Those traps were another source of adventure. Made of sticks and poles and jutting from the tidal zone out into the water they cunningly trapped fish that came in on the tide, leaving them to be picked out at will when the tide went out. We would sometimes help the fishermen catch the worthwhile fish and crustaceans and that was fun too. Sometimes, however, on a particularly high tide, dolphin got trapped there and small shark. Small but still sufficiently toothed to bite off the arm of a fisherman one day, who bled to death before he could be given medical aid. Once this story got around, we kids found the traps even more fascinating!

The Sunday beach expedition was usually a multi-family affair. On longer journeys we would go in convoy. Our favoured beaches were Jadini, in the south, which we believed had the best beach (from there to Diani) and where instead of a picnic we would have lunch in the dining room banda and my parents and friends would have a drink in the bar with Dan and Madeleine who were something of a legend for hospitality. But it was a long haul to Jadini and so our most visited beach was Nyali where the big hotel offered excellent hospitality, the great terrace overlooked the sea and the lido down on the beach provided drinks, snacks and changing rooms for day visitors. As well as an outdoor dance floor. And a raft just offshore. At other times we would go north to Shanzu, owned by my friend Margaret’s parents who were also famed for their hospitality. Or Whitesands, then owned by the Durwood-Browns. These were all casual sort of places with thatched bandas for the guests and a big, open-sided thatched dining room and recreation centre with bar. So simple, so unpretentious, so created for a perfect beach experience. At various times these places offered dancing and Whitesands had a radio that played the Hit Parade on Sunday evenings. It was there I first heard Elvis sing It’s Now and Never and we teenagers were shocked and disappointed that our badboy hearthrrob, fresh from army service, was now singing music of which even our parents approved!

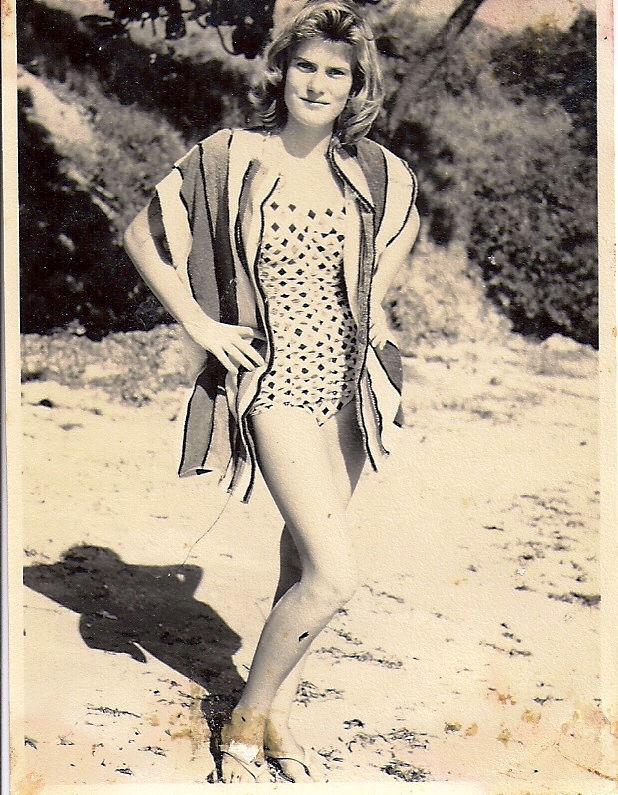

My mother and I on the beach at Jadini, about 1957. Jadini was a long drive from Mombasa Island but the beach strip along Jadini and Diani was one of our favourite destinations on Sundays.

How clearly I recall going home in the car, all passion spent, our skins roughened by sand and salt water, hair stiff with both. Home to hot baths and the modest Sunday night supper of salad with ham or tinned salmon, left ready by the cook before taking his day off. The slight sting of sunburn and the smell of calamine lotion as we crawled under our mosquito nets and fell instantly into the deepest and most satisfying of sleeps.

During school holidays, our greatest desire was to spend all day, every day in the water. At Nyali, or the Swimming Club just over Nyali Bridge, or, more rarely, the south coast beaches close to the Likoni ferry, Twiga or maybe Tiwi. What joy it was when we were old enough to have bikes that could carry us across bridge and ferry to be where we most longed to be. Independent, free, sunbrowned and skinny, needing only a soft drink and a cheese sandwich to get us through the day.

These simple whitewashed and thatched bandas were the typical accommodation of the day, simply furnished but comfortable enough to suit our modest holiday needs back then. And the sea was right at our door. (Photos courtesy of Beaver Shaw).

And then we put away our buckets and spades and our contented innocence and became teenagers for whom the beach had a very different interest. It was the popular place for birthday parties and teenage barbecue dances, scuffing the sand with our bear feet to Buddy Holly and Carl Perkins and, later, The Beatles, as rock and roll gave way to The Twist. We walked along the sand into our first love affairs, shyly holding hands, sneaking away from our parents and sullen when they insisted on knowing where we went. We still swam and frolicked but we were more self-conscious now, aware of our developing bodies, plagued by pimples and periods and embarrassing erections. Soon enough we had steady boyfriends and girlfriends and the boys had cars and it was down by the beach, or on the beach, that we lost our virginity, some of us.

Top: Myself on the beach at the Mombasa Swimming Club when I was fifteen. This was on the seaward side when you crossed over Nyali Bridge; a tiny, simple little building and a rather indifferent beach facing across the harbour to the Old Town. Its main attraction was that we could reach it easily on our bikes! Bottom: A year later and I’m on Nyali Beach with my BF Val Wheeler. We’d go to the beach with our boyfriends on Saturdays, change our clothes and shower at the beachfront Lido and then dance to a live band on the terrace of the Nyali Beach Hotel on the cliff above.

And then we were young adults and still the beach was our main weekend playground. We ventured further afield, north to Malindi and lovely Watamu, south to Shimoni which was all-but deserted in those days, always looking for a new and perfect and empty stretch of pristine sand. We took our picnic rugs and our simple food and often stopped in the little villages for cool madafu, watching while an obliging local cut the top off the coconut with a panga. We took along gear for spearfishing now, and hauled tanks for scuba diving, no longer satisfied just to stay within the protection of the reef but going into the blue deep beyond, where the bombies were.

There were only a dozen or so beachside hotels on the north and south coast in those days and they offered reasonable access off the main road but everywhere else you could only get to the water over rough sand tracks, the sand itself red or white depending on where you were, often so deep that we had to get out and help push each other’s cars through it. Old cars were all we young folk could afford – Morris Minors and Ford Prefects and battered Peugeots and Beetles with their engines at the back. No café SUVs for us! Our tyres were worn, our radiators prone to overheating and yet we got through. Lured by the siren song of turquoise water and the white waves breaking on the distant reef and a perfect day in the paradise that was soon to be lost to us.

For by the time we were taking our own children down to the sea on a Sunday, things were changing. The beaches, once so safe, were no longer places where we could wander alone. In the post-Independence boom more and more hotels were built, of much greater sophistication, and new people from around the world came to stay in them and new people from up-country came to work in them and today there are highways and bridges and buildings and shops and a degree of commercialisation that we could never have imagined, when we were young. There are camels on the beach, now. And vendors of tourist tat. And posh lounge chairs under the palms.

Yet the sand and the sea and the reef remain the same and children still play there, thrilled by what once thrilled the children of my generation. They have so much more than we ever had, in a material sense, and many virtual worlds at their command, so perhaps to them the beach is just one of many pleasurable experiences. Whereas for us, it was everything.

(I wish to acknowledge the photos used here of Thomas Ackenhausen, Robin Swift, Kevin Costa and Beaver Shaw, all contributors to the Kenya Friends Reunited Facebook site – without their photos this story would not be nearly so appealing. Thank you all).