This is the story of two young men, a mob of cattle and a year spent under canvas battling lion, rhino, drought, deluge and the many diseases of the African bush. All they had were a few basic supplies, a nervous labour force and their guns. It’s an adventure that Ernest Hemingway, that great lover of African adventure, could never even have dreamed of. And it recalls a time and a way of life that is long gone.

Kenya, like much of Africa, is a climate of extremes and it’s always, as Bob Lake used to say, one or bloody other! Bob is one of the two young men in this story, and the one who endured this adventure the longest. It is from his memoirs that the account is drawn.

In the three years up to 1961 the annual rainfall in Kenya fell from just over 304.8 millimetres (12 inches) a year to 76 millimetres (3 inches). . This severe drought caused problems for the cattle farmers in the Machakos district, south of Nairobi, and stock condition began to deteriorate. Then, as grazing turned to dust, huge herds of game – mainly zebra, wildebeest, gazelle and antelope, hartebeest and eland – moved out of the neighbouring Maasai reserve and on to the farms.

This led to a concerted effort to drive the wild game back into the Maasai country. Farmers and friends from the city gathered to shoot the vast herds and drive them back towards the railway line that ran between Nairobi and Mombasa. Bob Lake and his friend and neighbour Mark Millbank, the heroes of this tale, between them shot several hundred head in less than a month and drove many more than this on to other farms, where the shooting continued. Thousands of carcases were left for the vultures. It was brutal, bloody work and, in current terms, unacceptable but for them at that time, it was survival.

And, as Bob recalled, seventy years later: “It was all in vain. When I was out shooting with Major Joyce’s William Evans shotgun, on his property on the evening of April 11, 1961, I was surrounded by huge clouds of moths – as heavy as a snow storm. On top of the drought, the dreaded army worm moth had arrived. Within days our land was covered by millions of caterpillars, eating the last bits of vegetation down to the roots of grass.”

The caterpillars devastated acres of crops and pastureland as well as the greenery that kept the herbivores alive in the wild areas. They made the roads treacherous and stopped the trains from running. It was a plague of biblical proportions, consuming what little pasture had survived the drought. Something drastic had to be done.

Another local cattle farmer, Dennis Wilson, located 250,000 acres of ungrazed land at Athi Tiva, known then as the B2 Yatta Controlled Hunting Block and mostly uninhabited. It wasn’t good land, which is why nobody lived there; it was a dry, thorny part of the nyika that lies between the high plains country of the Athi, just south of Nairobi and the green hills that run behind the coastal strip. The nyika is not desert and it has rivers but it’s inhospitable country and home only to lion, rhino, elephant, cheetah, hyena, various tough-mouthed antelope and a lot of ground squirrels. Today it’s all been subdivided into small holdings and shanty villages and you have to wonder how they make a living there. Back then, nobody wanted it, except to shoot things for sport.

To save the herds around the Konza and Ulu areas, Bob and Mark set out to move 5,200 head of cattle belonging to nine farmers to the Yatta plateau, on to land given by the Kenya government as temporary grazing until the drought broke.

Each farmer provided herdsmen for his/her own livestock and contributed to the expenses of the venture on a per head of cattle basis. Bob was appointed manager and Mark as his assistant. Their only transport was Bob’s old, stripped down Land Rover.

For the two men, both 21, it was a great adventure – and a big responsibility. Athi-Tiva was home to the dreaded tetse-fly as well as ticks carrying cattle diseases such as anaplasmosis, east coast fever and redwater. The area had no roads, only rough tracks through the hunting block; nor were there any buildings or development of any kind.

The journey involved moving, at very quick notice, the 5,200 head of cattle south by rail for 150 km, then unloading them and walking them another 80 km north-east along the bush tracks and game trails. The herdsmen had to be constantly vigilant because the local Big Cat population soon got word that there was beef takeaway to be got for very little effort – it’s a lot easier to bring down a cow than a wildebeest or buffalo! Bomas – rough enclosures of thorny brush – had to be erected at night and the Wakamba youth taking it turns to be on guard were armed only with spears, clubs and pangas (machetes). Bob and Mark had rifles, shotguns and sidearms and the former were in constant use, to scare away predators or shoot for the pot.

When Bob, Mark and the labour force reached their destination a camp was set up near the Athi River – which was only a series of shallow pools in that dry season – and eventually Bob had the labour build him a long-drop loo up on a hillside where he could look out over the countryside – king of the world! Because he loved it there! Loved the whole, wild, hard life of it. A solitary man by nature, he was content to spend his days supervising the men and tending to the cattle, hunting and yarning with Mark, eating simple meals cooked over a campfire, going to sleep with the sounds of the bush in his ears. Lion prowled around the camp at night, attracted by the beef carcasses hung in one of the tents, covered only in a mesh to keep away flies. These steers, as well as various buck and antelope, had been killed to keep the camp in meat. A vigil had to be kept to prevent rhino from barging through the camp and knocking it down, there were a couple of near misses with elephant herds wandering past. Hyenas came to scavenge for any scraps or rubbish left lying around, their weird, wittering calls making it difficult to sleep.

They were not completely isolated. A few weeks after the camp had been established, a small village appeared further down the river. A few huts roughly put together from mud-daubed branches and corrugated iron, a dozen families, some goats and chickens. In the Kenya of those days, such habitations could appear almost overnight. Bob questioned the menfolk who blandly replied that they had squatters rights as the land was uninhabited. Bob pointed out that it was government land, set aside for hunting and not habitable anyway. Before long, a cow disappeared and then another. Bob’s men reported finding horns and hooves half-buried in the sand along the riverbank. Then food and small items were stolen from the camp. The Kamba herders went and searched the new “village” and found incriminating evidence. They threatened to drive the newcomers away and burn down their shanties. Things looked ugly and the two young white men had to try and calm things down; concerned also by the fact that the squatters were obviously starving in that savage country.

They shot some Grants gazelles as an emergency food supply, much to the disgust of the herders who clearly regarded these non-Kamba invaders from further south and east, lacking in all the bush skills needed to survive, as opportunistic parasites attracted by what they obviously saw as some sort of new farm settlement. More would come, they warned darkly, and Bob knew this was probably true. So he contacted the authorities in Kitui who eventually sent down an African police officer and his askari to deal with the problem. By now the number of squatters was steadily increasing, though they had neither food nor water nor protection from wild animals. A child had died, and it was reported that an old man, too, had died and been put outside the loose boundary of the squatter village, among the trees, where he was consumed by hyenas. Bob was skeptical about this story but the Kamba labour force firmly believed it and shook their heads at the young bwana’s tender British innocence.

In any case, the brief and lacklustre appearance of uniformed authority seemed to work and the squatters disappeared as quietly as they had come – one morning they were there and by nightfall the bush had swallowed them, leaving scarcely a trace.

Visitors, too, came from time to time to relieve the loneliness – friends, family, the other cattle owners, government inspectors and a vet bashed their way through the thorny terrain to reach the camp. All had to bring their own camping gear and at times the little canvas boma became quite festive – there would be rough shooting by day and singalongs by night; the Wakamba labour force would put on a bit of a dance. Better than that, the visitors would bring whisky, gin, beer, tinned delicacies, newspapers, books and magazines. But nobody stayed for long. Which was just the way Bob liked it. He was happy with Mark’s company and with learning more about the ways of the Wakamba and the wildlife all around. In the evenings they would read by the light of torches and spirit lamps. They turned in early because the work began at dawn, the days were long and in any case sleep was often interrupted by troublesome wildlife including, once, an invasion of Safari Ants which consumed everything in their path that wasn’t wood or stone or iron and could only be halted – though not completely stopped – by splashing around kerosene and petrol and setting it on fire, then battling to prevent the fire from spreading to the surrounding bush.

“Of all the dangerous things that happened in that year,” said Bob later, “That was by far the worst and it was lucky one of the watu gave the alarm before the ants got into the sleeping tents.” Trapped animals – and humans – have been devoured alive by the dreaded siafu – the remorseless, relentless Dorylus ants of Africa.

As it was, any food that wasn’t in a tin was consumed and a perilous trip in bad weather had to be made to Kitui the next day to re-supply; not just food but petrol and kerosene. “We kept a good supply after that,” Bob remembered.

Another constant threat was the scarcity of water and seeking it involved risk as the cattle were moved to the nearby river, and waterholes, and back. Water storage tanks were trucked in, small dams were built, pumps were put in place with great difficulty in and over the hard ground.

Bob and Mark were both keen hunters and good shots but had some narrow escapes – especially when an enraged rhino chased them, and Bob’s gun bearer, up a small and very prickly thorn tree. On another occasion, Bob and one of the senior herders were walking back to camp in the dusk when they got a strange feeling. They turned round to see two lionesses walking a few metres behind them. The men stopped. The lionesses stopped. Then, seemingly uninterested, moved into the bush. The men started walking again, turning their heads to see, after a few minutes, the lionesses back on the track behind them. Athi Tiva is not so far from Tsavo, where the famous pair of man-eaters once roamed and the area had always had a bad reputation for producing lion with a taste for human flesh. So the men were worried. After this continued for a few more minutes, and the camp still some distance away, Bob turned and shouted at the animals, who hesitated, lashing their tails, then, as Bob told it later, looking at each other as if to say “What’s that puny human think he’s doing?”

“I think, Bwana,” said the senior herdsman, a little agitated,, “That you should shoot them, not shout at them. These simba do not like to be shouted at.”

The lionesses were now only a few bounds away. Lion are curious creatures and Bob felt that if they meant serious trouble they would have just attacked without warning; perhaps they just wanted to know what these two strange two-legged creatures were, wandering through the bush.

“It was for all the world like they were two girls just out for a stroll and not particularly interested in us at all,” he always said in later years, when recalling the incident. “They knew where they were going and they obviously had no intention of getting off the track just because we were there. I got the feeling that if we’d just stopped and stepped back to one side they’d have passed us by with hardly a glance. But of course I couldn’t take the risk.”

So he raised his gun and fired over their heads. Even in those days, you couldn’t just kill a lion without a permit, except to save your life, though of course nobody would have known, in so remote a place. Nor blamed you, for there was no shortage of lions. Bob knew he might have to shoot them both and hoped they’d have the sense to bound away – which they did. Snarling.

“They stopped once and looked back at us,” he recorded in his game diary, “And I’d swear they were looking annoyed and reproachful. And then they melted into the bush and we didn’t see them again.”

Lions weren’t the only danger. When the rains came, which they did with shocking force, the almost-dry riverbed suddenly became a torrent, washing away bridges and tracks. This meant that the cattle could not be moved and Bob had to stay for longer than planned. Mark had gone by then, called to other duties, and two other young men came down, at separate times, to lend a hand. Two other young adventurers. But it all proved overly rough for them; too dangerous and lonely, and, like the occasional visitors, they didn’t stay long.

One of them, though, stayed long enough to give himself some grief. When the rain eased off the Athi ran more gently and pools formed among the rocks. Almost overnight, hippo appeared, just a few of them, lounging in the water with their watchful eyes above the surface by day, coming on to the riverbank at night to feed on the fresh new grass. Grass which was needed for the cattle.

The men tried scaring the hippo away and Bob’s new offsider, James, even went to Kitui – a long journey in the Land Rover – and brought back some cheap firecrackers which they set off gleefully – but after an initial panic and a lot of bellowing and splashing the hippos ignored them. Bob then shot one, and made biltong from the flesh and whips from the hide but while the hippos moved further down the river they didn’t go away.

James, who was in Kenya for a year after finishing Agricultural College, to gain experience before finding a job in South Africa, was a hot-headed 19 year old who came to look upon the small mob of hippo as a personal challenge. Though he had never done any shooting before, he took to it with enthusiasm and spent hours driving Bob and the African camp servants mad by practicing on a variety of targets – mostly old Heinz soup cans. Bob taught him rough shooting with a shotgun, for birds, and they bagged francolin and guinea fowl which made a pleasant change from the main diet of beef with maize meal and tinned vegetables.

But James’s mind was set on something bigger and as this was still a hunting block he was able to obtain a license to go for it. And the shooting of almost anything could be justified as necessary to conserve cattle feed. Bob had a good relationship with the Game Department, which trusted him to do the right thing, so he warned James several times to be prudent with his new-found skill.

Rain had made everyone’s work harder. No visitors could get through to relieve the tedium, this included the vet so Bob had to do a lot of the veterinary work himself; inoculating and dipping the cattle in the rough timber yards which had been hurriedly erected upon arrival, helping cows give birth, castrating young bulls. These were tough beasts with a strong dose of Sariwal in their bloodlines but they were still subject to the pests and diseases that makes raising cattle in Kenya such a challenge. Some of them were mauled in attacks by lion and leopard, which also took calves, others were bitten by snakes or harassed by hyena. Bob was out for long hours each day, fixing problems and encouraging the labour, many of whom had got fed up with the whole venture and wanted to leave, or had already gone.

James, young and heedless, went down to the river one evening and shot a hippo. He thought he’d missed because it disappeared under the water; when its head popped up he shot again. And again it disappeared, only to reappear a minute later. James decided to take a closer position and moved from behind his rocky vantage point closer to the water. And then he noticed three hippo carcasses floating along in the current, towards the camp. He’d shot three different animals! Half thrilled, half scared, he raced down the bank to have a closer look. Whereupon a couple of huge males came out of the water, straight at him. Instead of standing his ground and trying for another shot, James turned and ran towards the camp, screaming. Bob and some of the labour came from their tents to see what was up, in time to see the boy stumble and roll down the bank, on to some rocks. As Bob told it, the two hippos stomped about a bit but the sight of so many humans proved discouraging and they waddled back into the water to join the herd.

James had broken his right arm. It was put in a sling and he was given some aspirin, the only painkiller they had in camp, apart from whiskey. He had to endure the agony for several days before Bob was able to get him to Kitui in the Land Rover – an excruciating journey for someone with a bad fracture and a

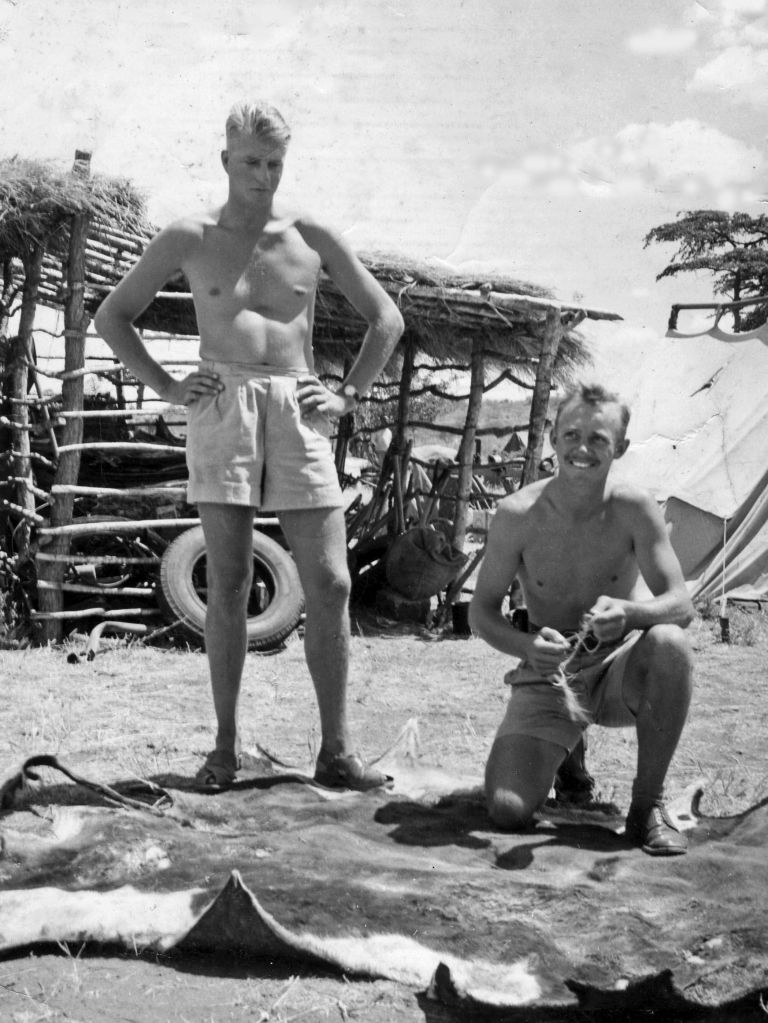

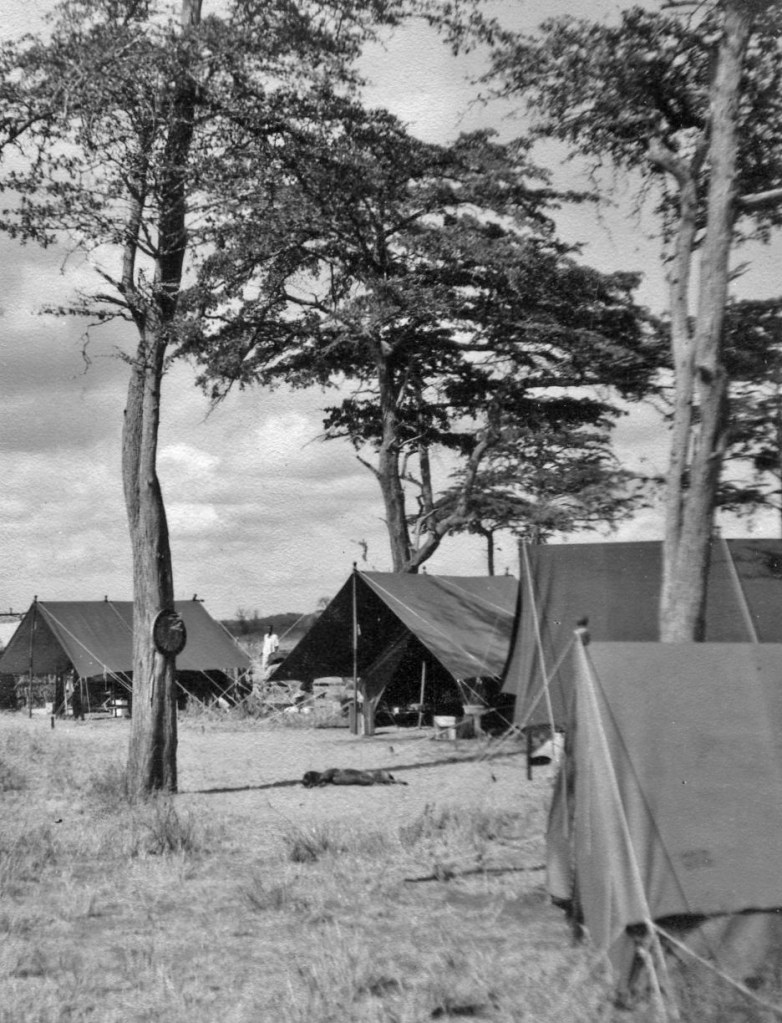

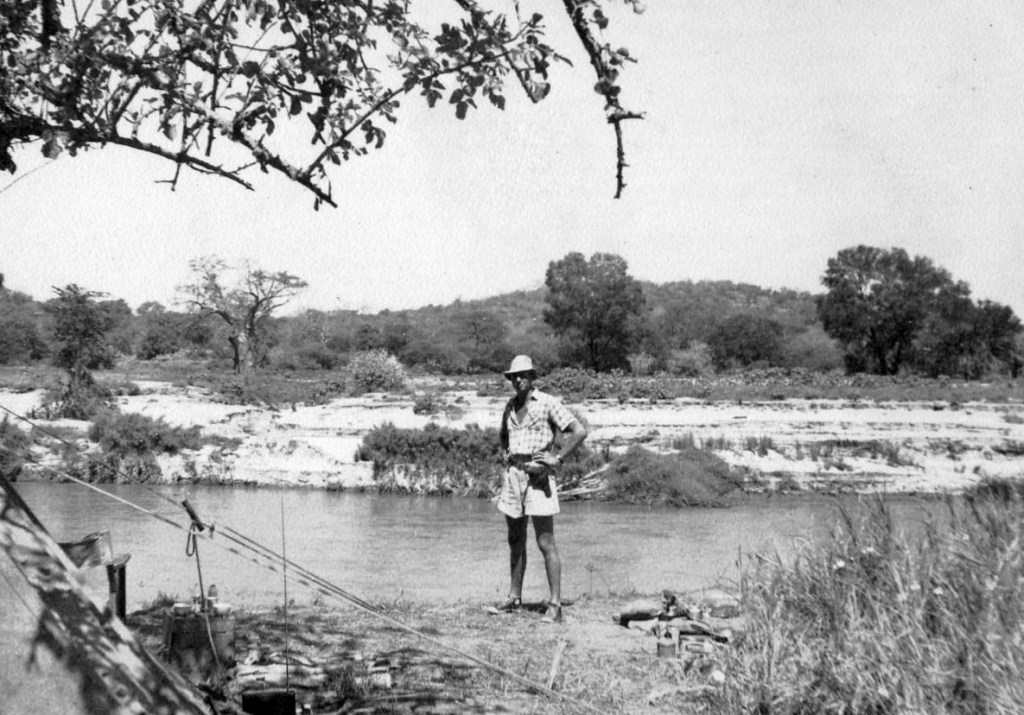

Down on the Athi River in 1961 From top left, Bob by the river near where his offsider James shot three hippo and then had to run for it; taking cattle across was always a risky business; James in the camp, just before his hippo hunting trip. Botom from left: When the drought broke and the rains came the river flooded and carried away the bridge; watering the cattle; an askari and his officer from Kitui questioning one of the squatters who mysteriously came to take up residence near the Athi Tiva camp.

Bob stayed for a year, living under canvas, happy in his comparative solitude and well-aware that he was undergoing a rare Boy’s Own adventure. Eventually, after the rains had come and gone and the grass grew quickly again on the plains, under the hot African sun, he and others took the cattle back to their home farms, with remarkably few losses considering the long period of privation and danger. Another long and difficult trek, another rail journey. And the acclaim of those whose livelihoods had been saved.

Bob Lake, my husband, lived to be 85. He had many adventures, both in Africa and in Australia where we eventually migrated and where we lived in some of the country’s toughest cattle country. Yet he always considered the Athi Tiva expedition the greatest adventure of his life and it’s a good job he wrote it all down because otherwise I wouldn’t be able to share it with you now.