I grew up in Kenya, East Africa at the ed of the colonial era – oh fortunate child! This was a childhood unimaginable today and those who shared it with me know exactly what I mean. Those who don’t, can read about it here.

Born of nostalgia and great love for a country that will always be in my heart, I offer a collection of small stories, to which I will add as memory prompts me. And others are welcome to add to this collection too.

There are many kinds of Africa and many different stories. These are mine

List of stories

. Leopard in her lap

. My first love affair

. Mboji and the chicken

. Mrs. R and the Tiger

. The great romance of travelling by train through the African bush

.The game drive – death on the African plain

. Life among the lions of Athi Tiva

. Ghostbusters of Mombasa

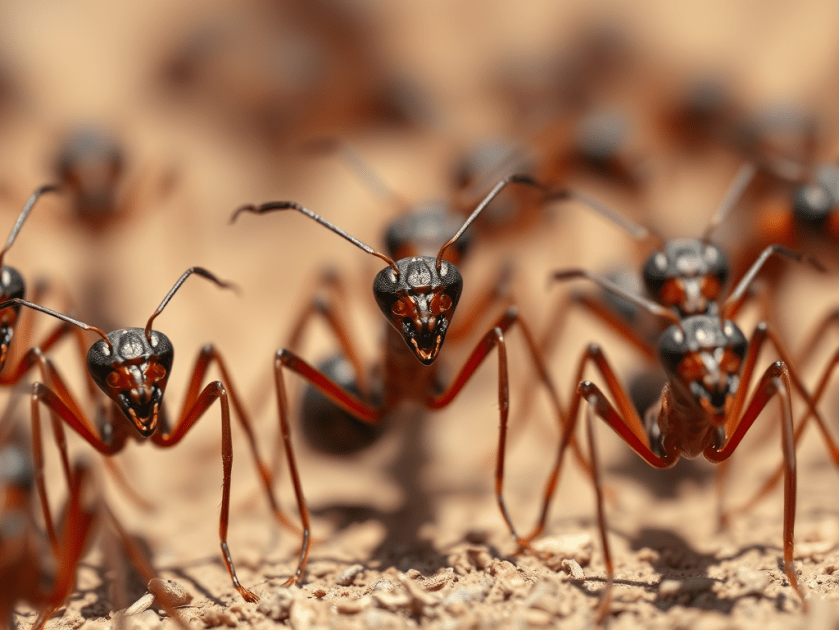

.The night the siafu came – an African horror story

. That old time rock and roll at the Mombasa Railway Club

. The Mombasa seafront

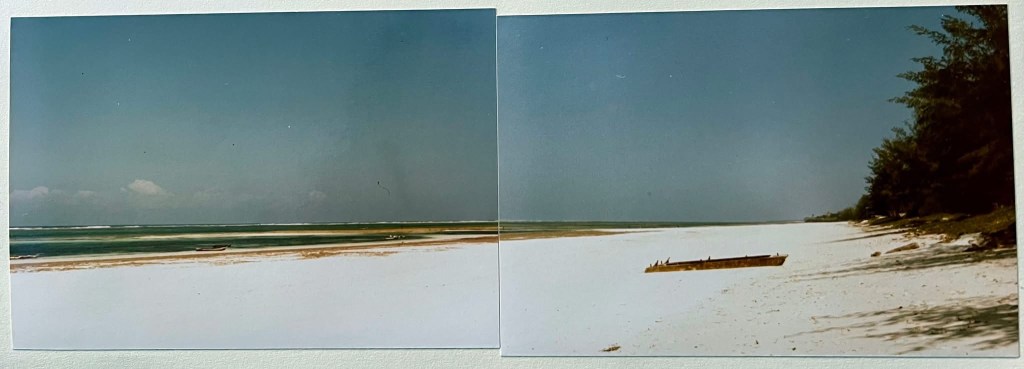

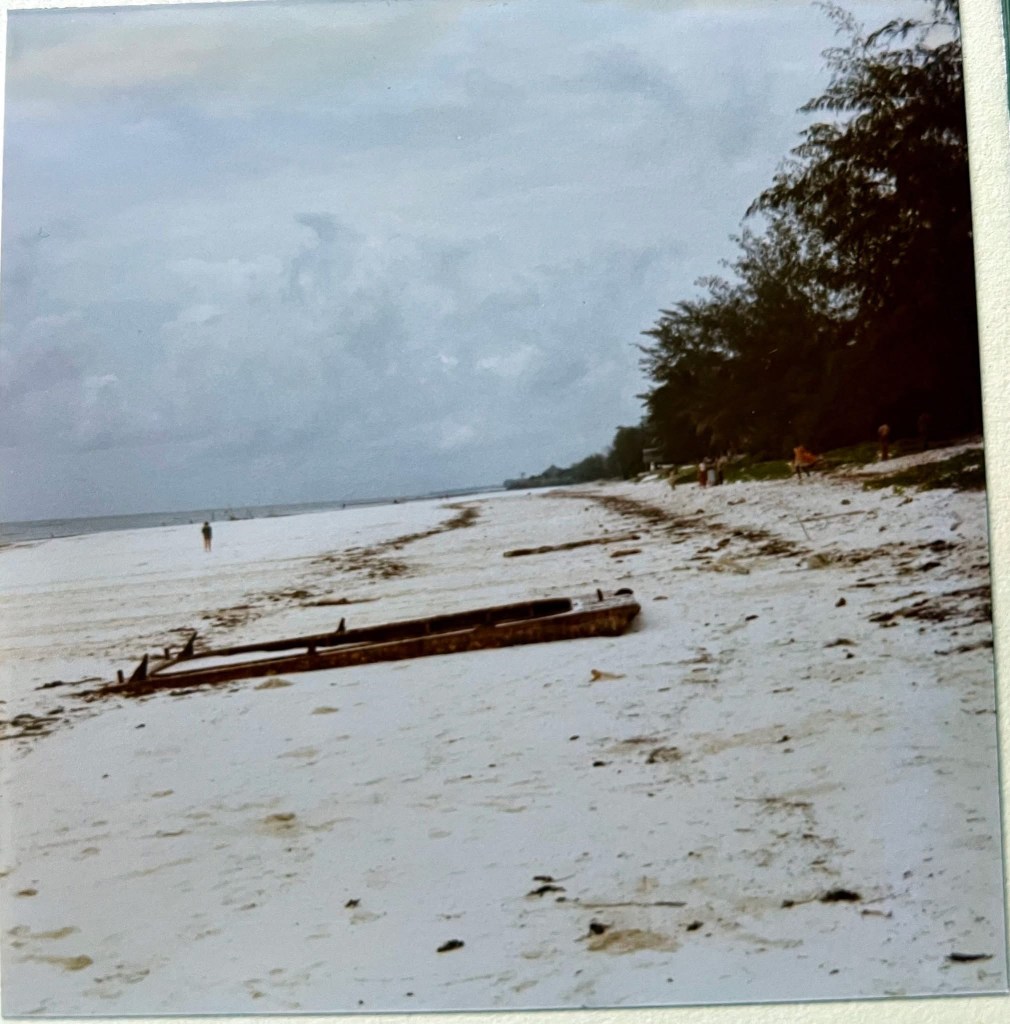

. The Beach – a paradise lost

. That old black magic – witchcraft and witchdoctors in colonial Kenya

Leopard in her lap

Remembering marvellous Michaela Denis

This is of course an AI generated image because all photos of Michaela are still protected by copyright. It is, however, not so different from the woman I remember, and true to my admiring childhood vision of her. She was, when not in bush clothes, very glamorous.

I walked down Delamere Avenue (as it was then known) one day, with my grandmother, and towards me came a woman trailing two cheetahs on a leash.

She was striking to look at, with glimmering red-gold hair and wearing a suit smarter than one normally saw on the streets of Nairobi, capital of colonial Kenya. But of course it was not her looks that impressed me, it was her two pets.

I knew who she was, of course, because I had already met her. As had my grandmother. This was probably the best-known woman in East Africa in the 1950s – the fabulous, glamorous Michaela Denis: adventurer, writer and, with her equally famous husband Armand, a television star. Kenya was more than a decade then from getting television but we all knew of Armand and Michaela Denis.

A few months earlier the Denis’ had visited our school and brought the cheetahs with them as well as a mongoose. The mongoose didn’t interest us much because they were common in Kenya and many of us had one as a pet at one time or another but the big cats were a thrill because unless our parents took us on safari, these animals were rarely seen.

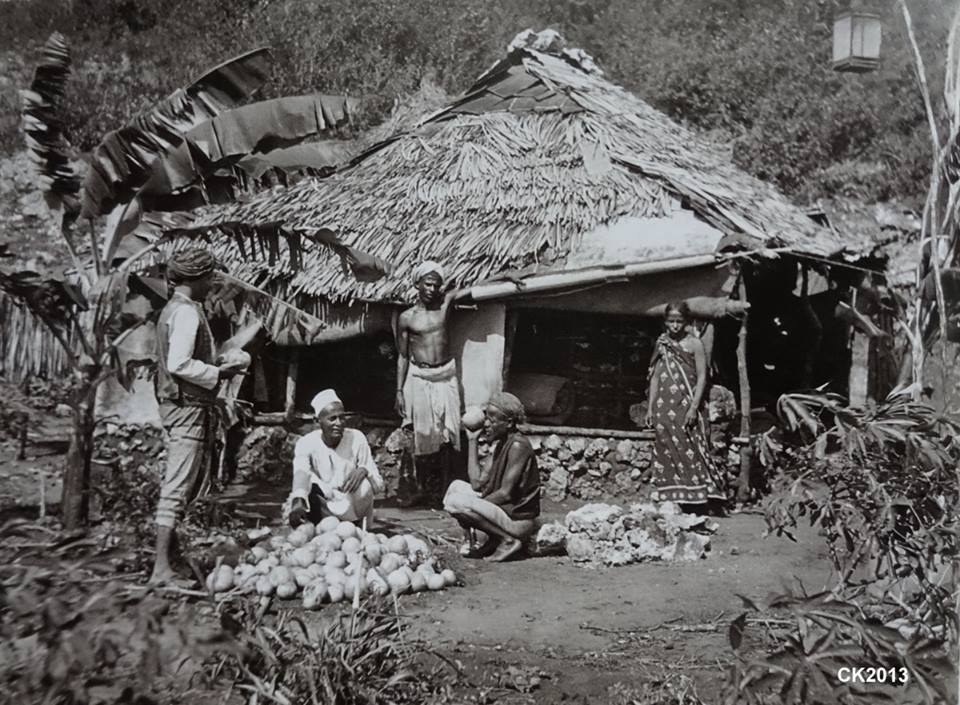

Though it is more than seventy years ago I still remember how much I loved Armand Denis’ talk; he was a big man, bulky around the middle, untidy hair, eyes kind behind his glasses. He showed us what was then called a “ciné film” on a cloth screen and in his soft Belgian voice explained the images ofwild animals and pigmies and other strange West African tribespeople, similar and yet different to the tribes of our own Kenya.

He was one of the first – and for a time – most famous of the world’s wildlife photographers, ahead, even, of the revered David Attenborough – and he lived in our backyard! He and Michaela had built a rather unusual house in the suburb of Langata which bordered the Nairobi Game Park. Here this ever-wandering couple maintained a menagerie of birds and animals because, like me, Michaela had been a little girl who adored wild things and collected everything from hedgehogs to beetles. Just as I did.

My grandmother knew Michaela because she had a friend who lived next door to the Denis’ home and while they chatted I kept my adoring eyes on the cheetahs. How I longed for a big cat of my own! A lion cub, a leopard, even a Serval cat as one of my friends had, but, most of all, a cheetah. They were said to be easier to tame than most wild creatures, good with children and domestic pets, able to be house-trained, better than dogs for hunting. My father used to laugh at the very notion of keeping such an animal in an urban environment. “They eat ten pounds of meat a day”, he told me. “Their claws are not retractable, like those of other cats, and they will scratch you. And just look at their teeth!”

I gazed at the cheetahs and they gazed at the horizon, perhaps seeking the great Athi plains which were only a short distance from that city street. Their indifference was total, quelling to the spirit.

“Can I touch them?” I whispered, shy in the presence of my goddess and her Olympian companions. “No,” said my grandmother. But Michaela, may her name be forever blessed, took my hand and placed it on the head of one of the cheetahs. I moved my fingers, scratching the scalp as I did to our dog. The fur, I remember, was very bristly and not as soft as it looked. My hand, still covered by Michaela’s, moved tentatively down the neck. The cheetah continued to stand there, perfectly still, unresponsive. The other one sat down with a grunt, as if resignedly making the best of things while these humans communicated with each other in ways mystifying to cheetah-kind and rather boring. People passed us on the pavement, some stopping to stare or say hello. Cars and bicycles went by only inches away. The cheetahs remained unruffled and apparently unseeing, like carvings on an Egyptian tomb.

I never got to keep a leopard. Or a cheetah. But I did have a monkey – a coup0le of them, in fact, at different times. Here is our monkey Peppy with my daughter Amanda – circa 1971.

After that day I went several times to the Denis’ house, with friends, to “play” with their wild things. Armand and Denis were very good with children, though they had none of their own. Besides the cheetahs, of which at one time they kept about half a dozen, they also had a young leopard called, from memory, Chui. Not very original as this is its Swahili name. The leopard was playful and firmly imprinted on Michaela who would hug and kiss it and let it lick her face. Those great canines, so close to her nose; those savage claws so close to her eyes! It was tame, didn’t seem to mind our presence, walked happily around the house and garden but we were not permitted to touch it. Leopards, we were told, were unpredictable around people, even when brought up as pets.

Nonetheless, Michaela preferred her leopard to the cheetahs. She told us it was warmer, more affectionate, bonded better with humans. Even though capable of doing much more harm. “Look into the eyes of a leopard,” she would say, “You’ll see feeling. A connection. Look into a cheetah’s eyes and you see nothing.”

Though I admired and even adored her in that pre-pubescent way of girls I didn’t agree with her. I looked into the eyes of Chui and I saw a creature that, even though well-fed and, it seemed to me, lazy because of it, would just as soon reach out one of those large paws and pull me within reach of its jaws. Just to see what I tasted like! I saw, I believed, a glimmer of hostility. Or avidity.

Whereas, to me, the cheetahs seemed to be always dreaming of somewhere far away; of running free on the savannah. Non-threatening but disinterested. Unlike with the leopard, we were allowed to play with them once they got used to us and never did I know them to be even the slightest bit spiteful. They tolerated our petting and would obligingly chase and pounce on objects towed on a string. They would even, sometimes, nuzzle our hands and rub against our legs, just like any cat. They were always happy to be fed by us.

But always they retained that aloofness. We just didn’t matter to them and they wouldn’t miss us when we left.

Michaela’s big cats were never caged, to my knowledge, merely contained at night so they wouldn’t wander while their humans were sleeping. Cheetahs are daytime hunters while leopards hunt mostly at night but well-fed cats of any kind don’t usually stray too far. Looking back, now, with the wisdom of years, I wonder whether, being hand-raised, they knew they would not fare well if they wandered over the fence to the national park beyond, where they would have to fend for themselves and their totally wild and free kind might not welcome them.

The leopard did sometimes go exploring. A friend’s father, who lived nearby, came home late on night to find a leopard sprawled across his stoep. He did all the usual things…shouted, threw things, sounded his horn. The leopard didn’t stir and nobody in the house, or in the servant’s quarters round the back, heard his shouts and horn-blowing so he had to stay there the rest of the night, sleeping in his car. When he woke, the leopard had gone.

It could, of course, have been a wild leopard because leopards were plentiful around the Nairobi suburbs back then – snatching dogs, frightening (though never to my knowledge actually harming) Africans on bicycles, always there in the darkness, swift and silent, rarely seen.

But, so the story went, a wild leopard would have run away if confronted by an angry and noisy human. Or even, if frightened, attack. The man swore it was Chui and many believed him. Complaints were made. The Denis’ denied it was their leopard but other neighbours had similar encounters and, so my grandmother told me, Michaela did take more care to keep her wandering pet confined because she was afraid that somebody might get trigger-happy. Many people had guns back then, because of the Emergency.

My family moved to the coast and I never saw Armand and Michaela again though their wildlife documentaries were sometimes shown in a Mombasa cinema and we saw the TV show when on holiday in England. “I know them”, I used to say proudly to my English cousins.

I never did get to own a cheetah. Or even a Serval cat. I am not in favour of keeping wild animals as pets and hate those American TV shows where people show off their tigers. There are, I read, more tigers in captivity today in the USA than wild tigers in India and, sadly, they may well be better off there. But it still doesn’t seem right.

A natural successor to Michaela, of course, was Joy Adamson and Elsa. But the Adamsons, living in a game reserve, always intended to return their lion to her wild condition. Which shows how times – and attitudes – can change, even within just a decade.

I re-read one of Michaela Denis’ books recently (thus inspiring this article) and now realise she was a silly woman in some ways and often wildly incorrect…some people would even find her descriptions offensive. But that is to judge the actions and opinions of the past through the filter of today and so, for her courage and kindness and glamour and passion for conserving wild places long before it became commonplace, she is still my hero!

Oh, and by the way, she couldn’t stand David Attenborough! Described him as a fool and a thief – apparently for pinching one of Armand’s ideas for a wildlife television program.

*************************************************************

My first love affair

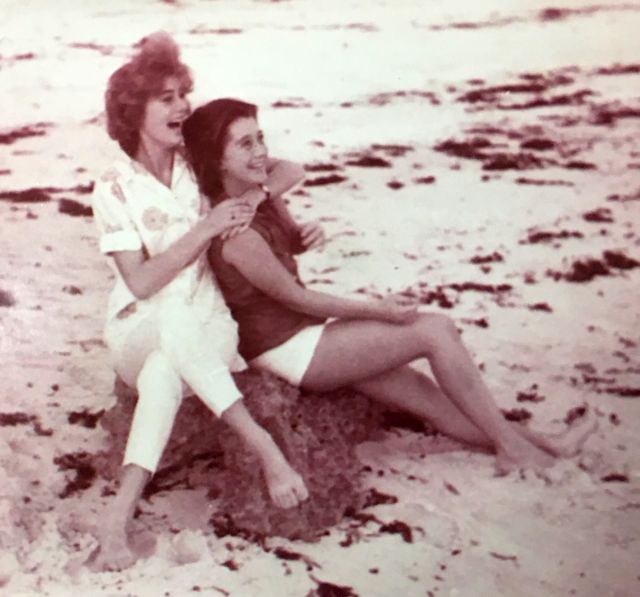

The sea was sparkling blue beneath the summer skies

And all alone with you I was in paradise

We wandered hand-in-hand, along the golden sand

Into my first love affair

That song was a big hit back in the late fifties when I was at boarding school in Nairobi. It was made famous, I think, by an English singer named Craig Douglas (possibly not his real name; very few English boys were called “Craig” back then); a milkman who had enjoyed a brief flare of fame before sinking back into obscurity. I feel I have a small claim on Craig Douglas because my cousin Susan, who lived (and still lives) on the Isle of Wight knew a girl who went out with him. Presumably while he was still a milkman. His songs, of which I can only remember two (the other is the more famous She Was Only Sixteen), seemed to echo the clopping sound of a milkman doing his horse-drawn rounds, or so my father once commented. Though by the late 1950s I don’t suppose there were many milkmen still driving horses, not even on the Isle of Wight.

For those of us who WERE about sixteen when the bland but boyishly pleasant-looking Douglas (he didn’t smoulder like Cliff or have the cheeky charm of Adam) enjoyed his brief hit-parade success, it was a song for our time and place. I was slightly younger but already well awake to the possibilities of love. It was no accident that Shakespeare made Juliet fourteen; we forget as we age that the most intense love is felt in our teens, when our hormones are most urgent and our emotions untempered by reality.

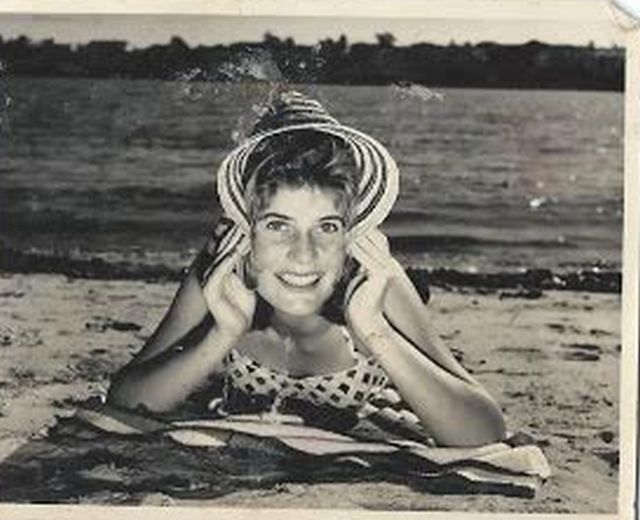

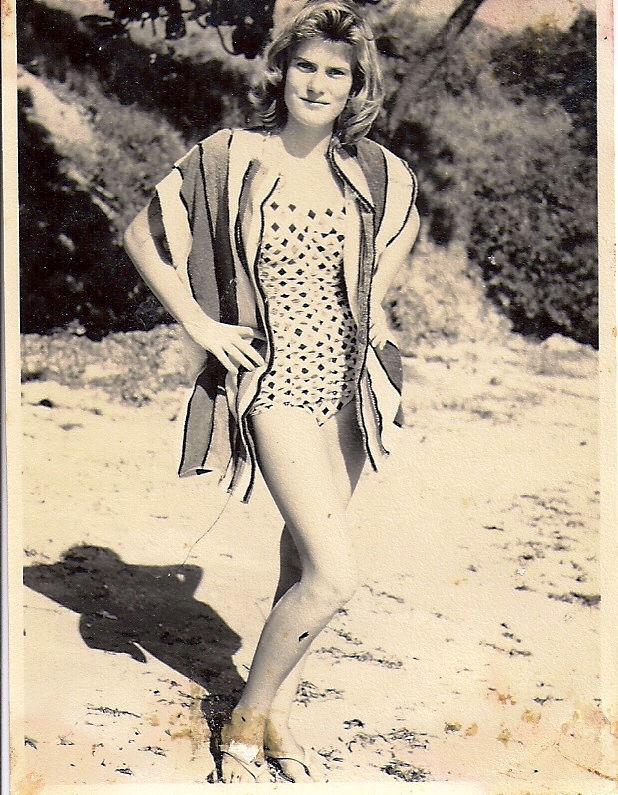

To live in Mombasa, back then, and walk along one of those endlessly pefect beaches, beside the Indian Ocean which ALWAYS sparkles, hand-in-hand with the boy of our choice (and who had, oh bliss! chosen us) really was paradise enow! True, our sand was white rather than golden, and all the better for that. Our cousins in England, poor pale things, could only enjoy that gold for a brief summer each year, and that fleetingly. Whereas we Kenya kids had our white beaches always there for our delight.

And so, for the teenagers of Mombasa, and those older than us who, for reasons which we found incomprehensible and faintly revolting, still insisted on romance in their lives, the beach was an essential factor in our love affairs. So it was for me, and I still remember those moonlight walks and frenzied gropings in the sand with great affection. But my first love affair was not with a boy – it was with Mombasa itself; the town and the coastlines north and south. Mombasa was the first great love of my life; like all great loves the memory still warms my heart and like all lost loves it haunts me still.

I still remember the day I fell in love. My father had taken up a new post and so we packed up the house in Nairobi and headed for the coast. We were, I remember, all ecstatic about this. Nairobi had come to seem grim with the dark shadow of Mau Mau still upon it. We didn’t doubt that the British Government and the stalwart nature of the settlers on their fortified farms would ultimately prevail over a handful of disaffected and witch-ridden tribesmen but there was nonetheless a strong sense of unease in the European community, sensed even by children at a time when children were seen and not heard and certainly not informed about adult affairs. It is not of course the done thing to say this now, but we felt betrayed by those we considered in our trust and wondered whether we could ever feel safe in that beloved country again. Too, the winds of change were beginning to blow just over the horizon, perceptible to those astute at reading political weather. Terrorism was all but defeated but those of us who thought we had won the battle were soon to find we had lost the war; within a decade we would no longer rule the land and our way of life would be gone forever.

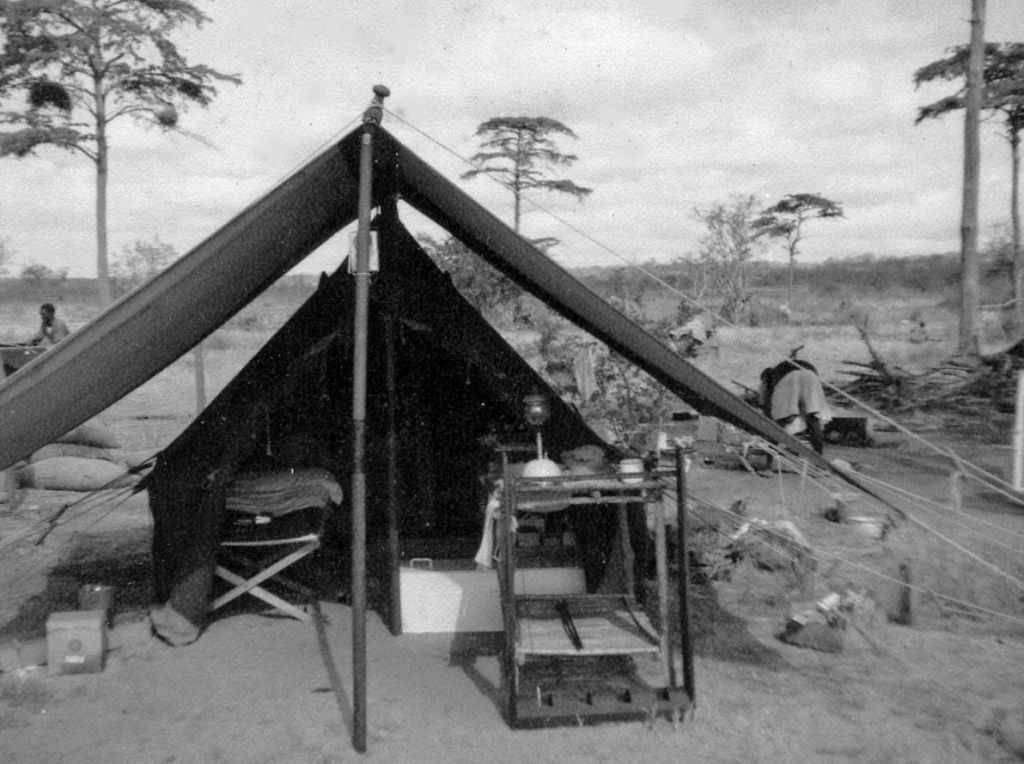

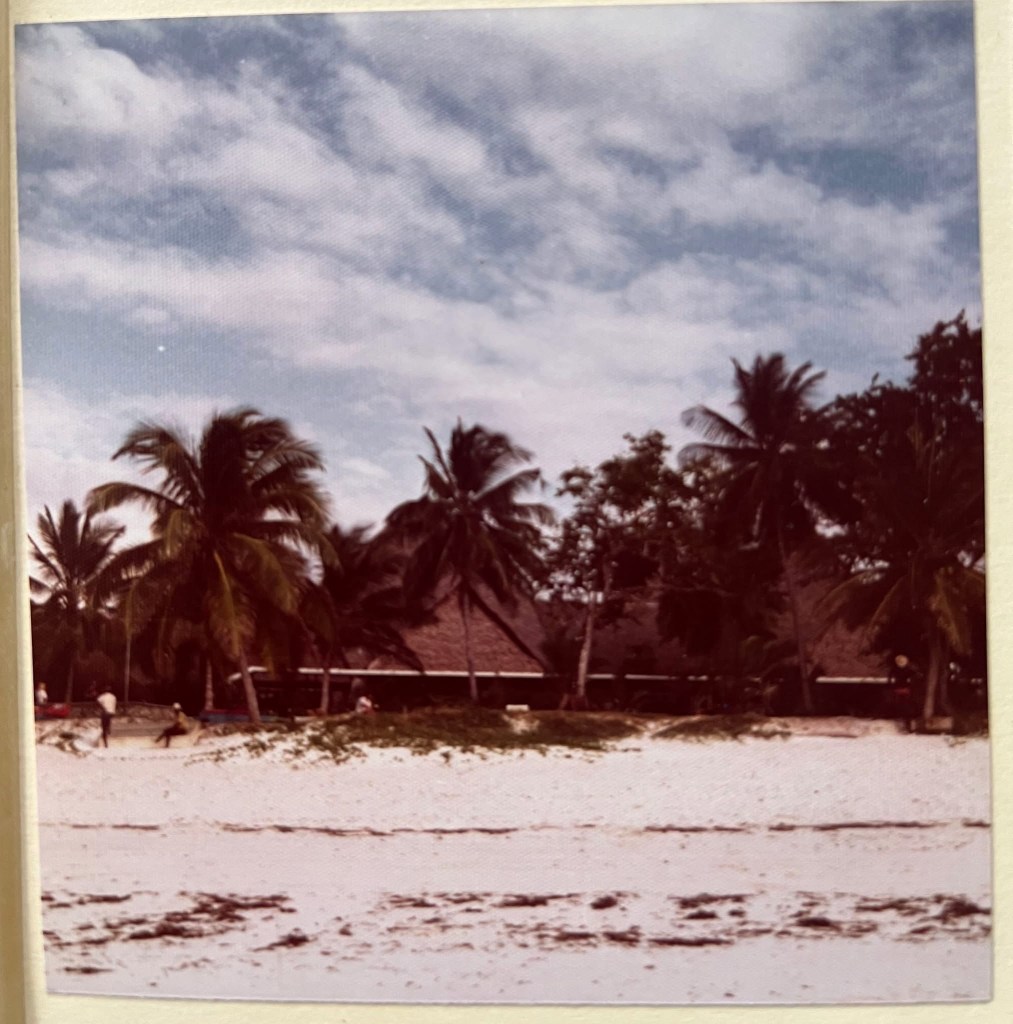

None of this weighed on my small family, however, as we took the red road to the coast. We knew what to expect because we had holidayed at Jadini where the simple thatched banda with its iron beds and primitive bathroom, sited between the jungle and the splendid beach, was all that up-country folk expected of a holiday in those simple times. But to actually live there with the beach forever at the door and the palm trees waving and the warm, moist seawind blowing over the island was unimaginable bliss. Especially after Nairobi which seemed colourless and dreary by comparison.

I should admit here that I never did really care for Nairobi. Most Mombasa people didn’t. Perhaps I associate the Kenya capital with boarding school (which I loathed and where I always felt I’d been exiled from my coastal heartland) and also the earlier period of Mau Mau with its curfews and alarms. Beyond that, however, I always sensed (and still do in memory) a darkness at the heart of the city which Ewart Grogan once described as “that miserable scrap heap of tin”. Of course it had changed a lot since pioneering days and had its revered icons – the Norfolk Hotel, the New Stanley bar, the markets, the game park at its boundary – as well as some fine social and civic developments such as theatres, shops, cinemas and Ledgco. For me, though, there was always a faint sense of depression to be found in the neat suburbs where so many of the houses were built of a grim grey stone, imprisoned by dense hedges of cypress or kai-apple. I felt this most keenly on those Sunday afternoons when I was taken out of school on one of the precious exeats by well-meaning aunts who took me to their homes and tried hard to feed and amuse me. The homes all seemed to be filled with a kind of sad Sunday silence . Even the gardens were darkened by overhanging trees which seemed vaguely threatening to me; occasionally leopards were seen in those trees, hunting the suburbs for dogs. Such leopards, the servant of one of my aunts once told me, were really were-creatures and therefore dangerous because they had no fear of people and were particularly fond of the flesh of children. He was a Kikuyu and thus believed strongly in such things and I believed too, because it seemed quite natural that Nairobi would harbor black horrors behind its sombre hedges.

The coast, by contrast, was all lightness and sun and happy glitter. We arrived there as eager new residents after the long drive which at that time was still an adventure. Traffic was low enough that when you passed another car, in a cloud of red dust, everyone waved and sometimes we would stop and exchange news of conditions ahead of us. Animals large and small crossed the road with insouciant frequency; everything from tiny ground squirrels by the dozens to buck and gazelle of various types, zebra and wildebeest on the Athi Plains as far as the scarp above Hunter’s Lodge, then rhino and elephant in the hot lowlands of the nyika. The mandatory stops were Kibwezi and Mtito Andei where there was a passable roadhouse; Voi if you needed fuel or felt you couldn’t go any further.

On this occasion we drove across the Causeway and on to Mombasa Island late in the afternoon, our car covered in red dust that also lay thick and gritty in our eyes and throats. Our first stop was the office of “Uncle” Peter. This was a courtesy title only; he and “Aunt” Kay were friends of my parents and no relation at all but it was common then for children to address close family friends by familial titles. The Japanese do it too, and the Australian aborigines. It’s one of those little social niceties that we have now lost in an age where even very small children call all adults by their given names.

Uncle Peter worked for the government and though I don’t know exactly what he did it must have been reasonably high-ranking because he and Aunt Kay had rather a splendid house on the seafront, next-door-but-one to the Golf Club.

And it was there, sitting outside his office, in the back of our brand-new albeit dusty Morris Oxford, that I fell in love. I remember the moment perfectly, though I can’t remember for the life of me exactly where we were. Somewhere around Treasury Square I should imagine. My father had gone inside to announce our arrival and while he was there I looked up and saw a coconut palm, heavy with fruit, leaning over the pavement. This tree, in all its slender elegance, repeated itself in shadow upon a white wall. And that was it! That’s all it took! Something about the tree and the quality of light and the feel of the air pierced my young heart as surely as Cupid’s arrow and skewered it firmly into the sandy soil of the Kenya coast. Six decades or so later I remember the moment quite clearly.

We then drove round the seafront where the usual afternoon breeze freshened the humidity. The grass on the golf course was bright green patched by the sandy bunkers. Palms framed the large houses up on the cliff, huge baobabs spread their sparse branches below. The sea was as blue as only the Indian Ocean can be on a fine day. A large ship in the dove grey and red colours of the Union Castle Line lay just off-shore awaiting the services of the small white pilot boat that bobbed over the waves towards it. Apart from one or two cars and a couple of golfers the whole expanse before our delighted eyes was devoid of human activity.

Just think, said Uncle Peter. I can walk out on to that course and play golf whenever I like – it hardly costs a thing.

Could you swim, I wondered? Swimming was new to me and associated with waterholes in the Athi River where you had to watch out for crocodiles.

Not here, said Uncle Peter. It was all coral cliffs and no beach. But you could walk round to the ferry and back one way, or to Fort Jesus and back the other way and hardly see a soul. And there were plenty of good beaches north and south of the island.

I was to do those walks many times, as child and adult. The seafront was to become focal to my life; a place to play in the baobab trees and the ruins of the wartime gun emplacements; to drive around for coolness of a Sunday afternoon and watch the bright-coloured Indian families debouch from their small cars; to buy peanuts in cones of newsprint from vendors pushing small carts; to ramble from end to end while pondering everything from failing relationships to major life-changing decisions; to swim away the school holidays in the Florida pool and, when it became a night club, to dance away the small hours. It was here that my beloved island met the sea head-on; beyond lay a world which, back then, I had absolutely no desire ever to see.

We spent our first night in the Manor Hotel. It was old and a bit fusty, with large and heavy wooden furnishings. My brother and I went to the first sitting for dinner, the only people in the dining room and the only children in the hotel at all. The waiters wore the standard uniform of white kanzu and red fez and served us with the kind, slightly irreverent deference with which African servants treated white children in those days. I remember there were four courses and that we ended with floating puddings which we thought a great novelty. Perhaps, like bread-and-butter pudding, they’ll make a come-back one day and be all the go in fashionable restaurants.

That night we slept for the first time under mosquito nets; these had not been necessary in our Nairobi house and we found them strange and a bit claustrophobic when the hotel ayah tucked us in. Funny to think that for many years after I left Mombasa I was unable to fall asleep easily because I missed the security of a net over me. Large ceiling fans stirred the air, another novelty. My parents, all dressed up to dine, came in to bid us goodnight. Isn’t it exciting?, said my mother looking happier than she had for ages because she was recovering from a serious illness that had left her thin and gaunt and very nervy. I thought it was exciting and knew myself already besotted by this new home, though I couldn’t have put my feeling into words.

Next morning I awoke and saw the sunlight glinting through the heavy shutters and, once again, that already-familiar silhouette of the coconut palm with its fronds gently shivering. The day would be full of new things; a house, a school, a different life. I don’t remember feeling even the tiniest regret for whatever I had left behind. I knew I was home.

In the years after that I came to know my island intimately, even to its furthest and least likely corners. I walked everywhere, to school, to town, to visit friends on the other side of the island. And where I didn’t walk, I cycled. It was nothing to us then to cycle all around the island and across the ferry to the south coast or over the bridge to Nyali. I’ve sailed down Kilindini Harbour and up the further reaches of the creekways beyond Port Reitz where even African fishermen didn’t go. I’ve explored the upper reaches of Tudor Creek, too, in the small and unstable canoe made by my father. There was a world of adventure for children in those places and nobody told us we shouldn’t seek it out, though the waters were full of sharks, especially around the Kenya Meat Commission and the port. I’ve swum across from the old Swimming Club to the Mombasa Club and back and cycled through the African townships and the commercial go-down area at Chamgamwe. I’ve trapped fish in the mangroves along the edge of Mbaraki and explored the forgotten caves near Fort Jesus. I’ve walked to town down Cliff Avenue when the Poinciana trees were in full bloom and wandered the streets of the Arab old town where street vendors were generous to children and old women swathed from head to toe in black bui-buis would scold us and tell us to go home.

Here, the old harbour could be glimpsed through narrow gaps between the pastel houses, busy with dhows in season, a glimpse of an earlier and more romantic epoch. We learned about this time in school; of conflicts up and down the Zinj coast, of Portuguese adventurers and Arab sultans, of slavers and missionaries and the explorers who ventured into the interior for ivory and the renown of discovering the sources of great rivers. The names of Speke and Burton, Grant and Thompson, Krapf and Rebmann were as familiar to us as were the names of Columbus and Magellan and Drake to children elsewhere. There were missionary graves just north of the island and the remains of the old Freretown slave market. Fort Jesus was a stalwart reminder of past battles; the small mosques dotted around the island a reminder that such battles had ended in compromise. We were taught that Mombasa meant “island of war” and Dar es Salaam meant “haven of peace” and that both had been havens for the pirates who sailed the waters from the Horn of Africa to Zanzibar, long before the slavers came.

I absorbed all this as if it was my birthright but strange to tell, when I learned all these things, it did not occur to me that there was anything extraordinary about the place in which I lived. I used to sit in the hot classroom at Mombasa Primary School, head on one hand, and dream of places that I considered truly exotic; Pago Pago, Rangoon, Rio di Janeiro, and great, slow-travelling rivers such as the Irrawaddy, the Brahmaputra and the Amazon. When I pictured pirates they were always walking planks in the Caribbean. Those were the faraway places with strange-sounding names of which I dreamed; it never occurred to me that the Kenya coast was in any way exciting or exotic. Like children everywhere we played at pirates and at one time our games were centred on an old wrecked boat that we found in the mangroves far up Tudor Creek. We shouted “ooo aarrhhh” at each other in the accents (or so we thought) of Devon and wore eyepatches and made swords out of timber and made each other walk the plank. We were always Blackbeard (a film that came out of Hollywood about that time) and never Sinbad. It was a triumph of culturism over geographical reality; who we were – little colonial Bwanas and Memsaabs – was more powerful with us than where we were.

Looking back like this it can be seen that I had soon learned to take my great love for granted. And yet I do think that one of the genii of the place had writhen its way into my spirit so that I “belonged” to the island in a way that my parents and other adults could not. Adults of my own kind, I mean, who had come to Mombasa too old to fall wholly under its influence. They liked it for its easy working hours, its obvious beauties, its pleasant life of clubs and sport and parties and beaches. I – and I know others who grew up there feel the same – knew something much older and deeper. It came to me in strange moments but the feeling is impossible to describe though it has something to do with Kundera’s unbearable lightness of being; a sublimity of soul envoked by a full moon over the sea, the sun shining in a certain way on a white wall, a dusty track between mbati-roofed shacks, the shocking contrast of white sand and green dune-plants and blue water, rain washing the squalid streets down the far end of Salim Road, the elegant stone fretwork of Islamic architecture, the rattle of the planks on the old Nyali Bridge, the song of the men pulling a ferry across a sun-splashed creek.

And there is a feeling more powerful than all the rest that today, long-exiled, I associate with Mombasa. It’s a purely personal feeling rather than one which others might share and though it manifests itself in the guise of memory it is not of any one particular memory but rather a synthesis of recollection that stands for a time and a place precious to my soul. I call it my “red lamp feeling” for want of any more telling description. There is a room, at that point of darkness which comes just after sundown on the equator, and in it are a mother, a father and two children. I think they are reading or listening to one of those old fashioned radios with a cloth piece at the front – I can’t quite be sure because, as I say, this is not quite a memory and not quite a feeling but something in-between. In that room there is a red-shaded standard lamp whose light shines kindly on them all and is also reflected in a nearby window. The room has window bars and the general appearance of my childhood home in Kizingo Road; beyond that I recognize and remember nothing. I have no idea what triggers this feeling/memory today but when it comes it washes over me with indescribable intensity – a sort of hot flush from the past which is at once painfully nostalgic yet deeply comforting. “This is absolutely the right time and the right place” it seems to say. I’m an atheist and a rationalist but if I believed in Heaven I would want it to be back there and back then for eternity!

So deep was my attachment to Mombasa that throughout my youth I could not bear to be anywhere else. I didn’t care much for going on long leave with my parents; the sea trip either way was fun but Europe – and England especially – seemed grey and cold and dreary to me in those years after the war. Who could find pleasure in bathing in a grey sea where the beach is full of stones, when they had known the soft white sand and coral pools of the Kenya coast? Who could enjoy the dull and rainy streets smelling of wet wool and the dank garden laurels of London suburbia when they were accustomed to dusty red-brown roads and flame-red poincianas and the beloved silhouette of palm trees? How could anyone LIVE in England, I wondered? France was a giant gallery of art and architecture intimidating to children, Italy a place of ruins both ancient and modern inhabited by voluble fat women in flowery penziones who fed and minded my brother and me while our parents went out to dine in little cliff top restaurants overlooking the sea. Well if that’s what they wanted they could do it just as well at Nyali Beach was the way I looked at it then. All I wanted was to get back home where I belonged.

Even worse was being sent up-country to boarding school. Again, it was as if all the colour had been taken from my life and I hated it! I pined and wilted and begged my parents to let me stay and finish my schooling at the coast where the old Loreto Convent seemed to embody the spirit of every such school in every tropical colonial outpost, its deep verandahs shaded by frangipani and Poinciana trees, the sound of chanting softening the wet and heavy air. Eventually I got my way; on the day when I was sent home by train, in disgrace, though fearing (justifiably!) the retribution that awaited me all I could think of was that I would soon be back in Mombasa Island’s safe and sunny embrace.

And so the years passed and in my memory we danced them away with no concern for the future. Dancing was very much part of our lives; we started when young at the Railway Club’s school holiday Wednesday night rock ‘n roll sessions for teenagers , graduating to the Sports Club at New Year and the Sunday night live band out at Port Reitz. While my parents and their friends danced sedately at the Chini Club we younger folk did the twist on the floor under the stars at Nyali, or at the Sunday tea dances further up the coast, or at private parties on Saturday nights. Nightclubs opened, seedy and mildly wicked, and we danced there, too. We danced on New Year’s Eve and at Government House on the Queen’s birthday, and on board ships in the harbor. We drove to the dances in open cars with the soft wind of the ocean blowing our hair, and back from them late at night on the long, empty roads, spoiled children of Empire who would dance forever as long as they never left the Enchanted Isle.

Yet leave we did, most of us. The problem with all great loves, whether they be for people or for places, is that they change. And so do we. When this happens we either try and accept the changes and grow old together, wrinkles and all. Or we part and go our separate ways. When Independence came to Kenya and Mombasa began to change, not dramatically at first but in small, insidious increments, I knew I couldn’t stay. The reasons for leaving were all commonsensical but in my heart I felt that a serpent had entered Eden and I and my kind were being cast out and that Eden itself was about to be despoiled. Fanciful, I know, but then love is not a reasonable emotion.

Sad to say, so disenchanted had I become with my Enchanted Isle that when I finally left I did so without a twinge of sorrow. All I can remember is driving one last time through to Tudor to say goodbye to a friend and thinking how dull and flat everything seemed on a Sunday afternoon. The very palm trees that I’d always so loved seemed to droop with lethargy. I, by contrast, was filled with the vigour of seeking new and larger horizons and I felt quite sorry for those whom I was leaving behind! It was only later, quite a bit later, that the soft and sweet memories stole over me and I wept for all I had given up, even though I knew that what it was I missed was gone from me forever, stolen by time as well as politics.

In time I learned to love a new land where the beaches, like those of my childhood, go on forever. True the sand is not quite so white nor the sea quite so brilliantly aquamarine; the coconut palms have been planted and there is no protective line of reef. Yet still it’s a fine place where I can wander the tideline safely and alone, and where I can still recapture something of my magical childhood.

Because the essence of your first great love is that you never forget it. Never, ever, quite manage to tear it from your heart. In memory, Mombasa is never very far from me and because I have not been back that memory is pristine and preserved in time as perfectly as an insect in amber.I began this story with a song and I’ll end it with another; one that, when it came out, I felt had been especially written about Mombasa. When I sing it today, it still makes me cry!

Oh island in the sun

Willed to me by my father’s hand

All my days I will sing in praise

Of your forest, waters your shining sand

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Mboji and the chicken

Our cook, Mboji, was, by Kenya standards, better than average at his job.

There is a tendency today among the ci devant bwanas and memsaabs to eulogise the skills of the cooks of their youth, and to remember the meals they prepared more fondly than is warranted. The truth is, we ate very plainly in those days, at best, and very badly indeed, at worst.

My parents were both rather keen on their food and demanded a reasonably high standard of their cook. By “reasonably” I mean that meat should be tender or at least chewable and cooked to the right degree, neither overcooked in the case of beef nor undercooked in the case of pork. Vegetables should not be boiled to a fare-thee-well. Custard should not be lumpy. A cook should have a reasonable repertoire of recipes, be prepared to try new things and have some understanding of how to creatively use condiments and spices.

Mboji met those standards, which was more than could be said for the mpishis employed by some of my parents’ friends. Down the road lived my friend Irene, whose mother was not very interested in housekeeping and whose father knew better than to protest. They employed a truly awful cook. His idea of that perennial nursery favourite of our youth, macaroni cheese, was to use spaghetti instead of the more usual macaroni, cover it in a lumpy cheese sauce and then bake it in an oven until it dried out to the consistency of a pudding, with the pasta all crisp and crackly. We’d pour HP sauce all over this and I, for one, used to think it yummy and be very happy to be invited down for supper on a Sunday evening (as with most people we knew, they had dinner on six nights a week but a light lunch – usually out somewhere – on Sundays and “supper” in the evening). My mother, however, ate it once and could never be persuaded to do so again. This cook also used to do a “curry” every Saturday which, like most Kenya curries served in European households was a stew with curry powder added. I liked this a lot because it had potatoes in it, which Mboji’s curries did not have. Mboji, in fact, made a pretty good curry. I say this after years of learning about and cooking Indian food. His curries would not have passed muster in an Indian household but at least he used fresh spices and authentic condiments and they bore an acceptable resemblance to the real thing, especially his prawn pulao. Mboji did not believe in putting potatoes in a curry. He would serve them as a side dish, cooked in ghee with appropriate spices.

I had another girlfriend, Ann, who lived across the road, and she also had a mother who was not interested in housekeeping. In fact this woman had no interest in her family at all and, in my memory, was rarely home. I shan’t mention her name here because she was very well-known in the Mombasa of the late fifties and early sixties. Her husband did something obscure in the PWD and they were rarely seen about together. Their bungalow was dreary beyond belief, furnished only with the ugly PWD furniture common to many Kenya houses back then. My mother would have had cheerful covers made for the furniture and put vases of flowers everywhere but in this home there were few books or ornaments; no pictures on the wall except a calendar; no comforts anywhere. The bedrooms were bleak and barely furnished beyond a couple of iron beds in each. I stayed the night there once, as girls do even though they are only a stone’s throw from home, and hated it. Even though I wasn’t much concerned with comfort and decor at that age and thought my own parents rather finicky because one couldn’t drop food on the floor or put your feet on the furniture in our house.

In my friend’s house, the cook-cum-houseboy (they only had one servant; how odd we thought that!) was worse than awful. He barely cooked at all but seemed to be employed merely to throw an occasional broom around the painted concrete floor (no rugs) and open a can. Every time I ate there, we had baked beans on toast. Now this was a popular dish in our house, too, at least for my brother and I who were of course fed separately in the evening from our parents (at least until we were in our teens). These suppers consisted mainly of baked beans on toast, sardines on toast, tinned spaghetti on toast, cheese on toast and scrambled egg on toast. We did sometimes have other things – I remember tinned salmon salad and also tinned corned beef (which we called “potted human”) and salad. But it’s the somethings-on-toast I remember because these were our favourites and, like most kids, we detested salad.

Ann’s family cook, however, rarely seemed to adventure beyond the baked bean for the evening meal and they didn’t always have a hot lunch, either. The mother, a career woman, ate out a lot, and the rest of the family survived on tinned stuff and the occasional flavourless stew or – when spoiling themselves – a leathery roast topside or chicken.

So I was considered very lucky by some of my friends and my home a haven of comfort, with good meals and well-trained servants. They loved to come and stay over, or just have a meal, and my mother – and Mboji – were always happy to lay an extra place at the table.

When I look back, our meals were very simple. The delicacies we take for granted today were just not available to most of us in those days, or cost too much for the average household. Meat was abundant and cheap but usually of poor quality and tough. I remember Ginger Bell’s butchery in Mombasa, where the carcases used to hang overhead, so that I would avert my eyes when buying meat there, which I did when I grew up and had a home of my own to run. He was a good butcher but the quality of the meat, while flavoursome, was not what we would tolerate today. Every week Mboji used to order a large piece of topside and this was roasted on Monday and served with roast potatoes and usually fresh carrots and tinned (later frozen,) peas. Fresh peas, like so many other “English” vegetables, were difficult and mostlyimpossible to get in Mombasa. Cabbage was rare and cauliflower almost unknown. My parents used to reminisce happily about the brussels sprouts and parsnips of England, which were only well-flavoured if they’d “had the frost on them” . As neither of my parents knew anything about horticulture and had never grown a vegetable in their lives, I doubt they really understood what this meant, but I remember them saying the same about “new” potatoes.

Back to the beef – this was our standard weekly fare. On Tuesdays we had cold beef with salad and boiled potatoes. On Wednesdays it was served as shepherd’s pie. Thursdays were a bit exciting because this was Mboji’s day for spontaneous creativity and we never knew what we’d get, though it was always delicious. I remember the remains of the joint being cut into thick slices and recooked in the oven in a casserole dish, with a flavoured sauce made from tinned tomatoes and onions poured over it. Or chopped into a tasty hash and served with rice. Friday’s meal was often fish, not because we were Roman Catholic but because it fitted in with all the other meals. Fresh fish of course was freely available in Mombasa, from the markets, but when frozen food became available we used to have Tilapia from Lake Victoria, packaged and frozen by Tufmac. It seems wicked now that with all the parrot fish and kingfish in the sea at our door, we ate frozen fish! But so we did sometimes, served either grilled or in a mornay sauce. We never had it fried – for fish and chips we went to the Rocco fish bar in Kilindini Road and either ate it there or brought it home wrapped in newspaper. That was often a Sunday night supper and we considered it a great treat.

Saturdays my parents either entertained or ate out. When entertaining, the meal would usually be soup, then something with prawns and/or fresh fish, followed by a roast of pork. Pork was a great treat then, brought down from up-country. If my parents were REALLY putting on the dog we had a leg or saddle of Molo lamb. Sundays were always less structured in our household, due to it being Mboji’s day off. Mukiti, our houseboy, used to do the honours instead but he could only cook a bit and in any case we usually went to the beach for the day. Either to picnic, when we children were small or, when we grew up, to lunch at one of the beach hotels. The Sunday evening meal was always quiche, which we called egg-and-bacon pie back then, or, as stated, fish and chips or a takeaway curry from town. But Saturdays live on in my memory as the special day of the week for meals. Of course, we children didn’t take part in the dinner parties when we were small and were given the usual early supper – but on Saturdays we got a treat. This was usually sausages, but not any old sausages. These were Walls skinless sausages and we adored them! My father did too so we sometimes got sausages on other days too – but usually they were a Saturday night treat for the kids.

Best of all, though, were those rare Saturdays when my parents were neither going out nor entertaining. We usually had a curry then, with all the trimmings. Or else we had Mboji’s signature dish – roast chicken. My father maintained to the day he died that Mboji’s roast chicken was the best in the world and it, too, was served with all the trimmings – bacon on the top, roast potatoes, assorted vegies, sage and onion stuffing (from a packet) bread sauce (home-made the traditional way) and gravy. We sometimes ate chicken in other ways; in curries for example, or a casserole. These were the tough village birds that were brought live to the house, purchased after much argument with the sellers by Mboji, and then killed by Kaola our garden “boy” under the Neem tree near the kitchen door. When we had roast chicken, though, the bird was especially purchased from our grocers, Beliram Parimal, and for a higher price that guaranteed it to be tender and succulent. The comparatively high cost is what made it a treat for special days.

The smell of that chicken roasting had us salivating all morning as it drifted right through the house and across the garden. To this day it remains my favourite dish, even in this age of TV superchefs and cooking contests and sundried tomatoes and aioli and truffle oil. Mboji, dressed in his spotless white uniform and beaming with pride, would bear in his kuku on a large platter, and we would all murmur with delight and anticipation. Visitors (for we sometimes had close friends or casual visitors to lunch on Saturdays) would be similarly impressed by the sight of this glistening, golden brown bird on its big white plate. Few other homes in Mombasa, we smugly believed, could boast such a bird – or such a cook. My father would carve with ceremony, legs for the children, breast for the adults, the parson’s nose (for some reason considered a delicacy) retained for himself. I longed for the white breast meat but knew it as a right of passage that one day I, too, would be serving up such a bird and would be able to eat whichever part of it I liked!

Mboji worked for us for many years, but not without a brief hiatus. He was a Taita, from near Voi, so was able to get back to his family often, apart from the usual two weeks holiday a year. We had quite large servants’ quarters and the wife and two small girls came down to live with us from time to time, but Mboji preferred them back in the village tending to the family plot. He seemed always to get on very well with our other servants, who were Wakamba, but perhaps he was lonely because though in all ways clean, cheerful, competent and decently-behaved he did occasionally go on a bender and my father would be called in the middle of the night to go and bail him out of the local clink. For the next few days he would skulk about the kitchen, reddened eyes lowered in shame, having assured my father he would never disgrace us all again. But of course he did, though never more than once a year. One year, however, when my father’s responsibilities for the finances of the province were weighing heavy, he received the familiar call in the middle of the night and THIS time he refused to go. Instead, he left Mboji to enjoy Kingi Georgi’s hospitality for another day before paying the fine, and then he sacked him. We were all very shocked and my mother was livid; where, she said, in the tones of The Mikado’s Kadisha, Will I Get Another?! But my father would not be moved and the household went into a sort of subdued mourning because Mboji was, to us, part of the family and we missed him. We also had to make do with Mukiti’s cooking for a few days, with some necessary but reluctant assistance from my mother.

Then, with as much self-assurance as an angel sent from Heaven, Andrea appeared. He was from the Congo, of some tribe unknown to us, and spoke French as well as a very correct Swahili in a strange accent. He came to us by way of a friend of a friend, and was said to have worked for the French Ambassador in Nairobi, or at least for a Frenchman of high standing in the colony. Certainly he had impressive references. My father took him on at once and our mealtimes were transformed! Andrea was not just a cook, he was a CHEF par excellence. His cassoulet was a poem, his casseroles sublime. His pastry was perfect and for afternoon tea we got éclairs instead of scones; tortes instead of Victoria sandwich or fruitcake. And as for his soufflés…well…let me just say that I have never tasted anything so light and perfect since – certainly I have never myself quite managed to attain that standard. My mother was in ecstasy and her reputation as a hostess shot up to new heights. To be invited to our place and eat Andrea’s cooking was considered a great privilege. My mother reviewed her entertainment schedule and decided she could risk bigger and bolder dinner parties. Andrea responded to this with great enthusiasm, helping her plan wonderfully exotic menus, giving her new ideas that her simple English (well, and Italian too) soul had never dreamed of, telling her of a fine foods emporium in Nairobi that imported cheeses from France, at a cost. For the first time we tasted brie and camembert. It is not an exaggeration to say that our family was the envy of Mombasa – or at least the European section of it.

Oh, and Andrea could do a pretty good roast, too. True, it had flourishes that were strange to us. Gone was the familiar weekly joint of topside, replaced by sirloin served very rare. Lamb, too, that most precious of meats, was served up gigot in style and rather more rare than my father liked. Pork, for some reason, Andrea despised. And yes, he could (at our request) roast a chicken. And a very fine chicken dinner it was, too. And yet, as my father used to say, it was not QUITE as good as Mboji’s. My mother vigorously denied it but secretly we kids agreed with our father. Maybe it was the garlic, which though not entirely strange to us was nonetheless used sparingly in our household. Maybe it was the exotic stuffing – chestnut puree, celery and walnut – that took the place of the dear old packet sage and onion. Maybe it was the lack of bread sauce, which Andrea did not know and refused to make when it was explained to him.

We children, too, benefitted a bit from Andrea’s haute cuisine though he made it obvious he was not frightfully keen on wasting his talents on the nursery supper table. Gone were the baked beans (le baked bean! Quel horreur!) and the tinned sardines. Instead we got eggs scrambled in orange juice or poached over spinach (which we hated). Sardines were served rather deliciously in a baked dish over potatoes, which we loved.

There was, sad to say, a definite downside to all this culinary euphoria. Andrea, like all great chefs, was temperamental to a fault. He despised the other servants and bossed them around in a tone as deadly as a cobra. In fact he despised our whole household and made it clear he was accustomed to better things, like some Upstairs, Downstairs butler who finds himself forced to work for a socially inferior family. He launched into furious tirades which went right over my mother’s head; for one thing she was rarely around to hear them and, when she was, dismissed them airily as “temperament”; understanding neither French nor much of Andrea’s high-flown up-country kiSwahili she really had no idea what he was going on about. She continued to be his champion, despite the fact that he was always criticising the kitchen and bullying her into buying expensive culinary gadgets that had to be purchased in Nairobi or even from overseas. I remember an omelette pan that had to be ordered from Johannesburg.

Andrea was also rather fond of fitina – ever ready with a complaint. These were generally about the other servants or we children, especially myself. He was quite gentle with my often-sickly brother but found my rambunctious tomboyish ways not at all to his taste. He particularly disliked me going into the kitchen and helping myself to cheese from the ‘frig, or sitting on the back stoep and chatting with Kaola, who was a great friend and occasional companion in adventure. Andrea’s complaints were made to my father, generally when he came home from the office at lunchtime, and always began with: “Ah Bwana, shauri kidogo….”. My father learned to dread these complaints which always led to unpleasant confrontations with either his staff or his children. In any case, after a short honeymoon period of fabulous feasting, he was not quite so keen as the rest of us on our new cook. My father liked French food well enough, in a restaurant, but at home he preferred plainer English fare. Also, Andrea (who had demanded, and got, higher wages than Mboji and probably any other cook in Mombasa at that time) was proving very expensive. The grocery bill had shot up and there were always extras being brought in from elsewhere. My mother did not like to rein in Andrea’s enthusiasm because he sulked if thwarted and implied that no hostess of HIS wide experience would quibble about such bagatelles as the cost of importing pate de foie gras direct from France – or at least from Leopoldville!

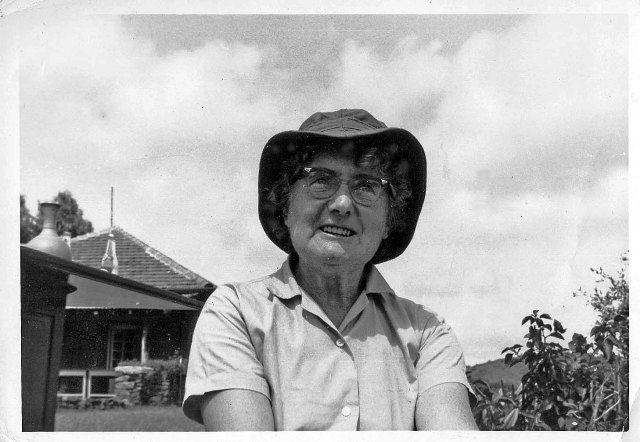

Certainly we were eating well, but our formerly happy household was becoming a place of strife. The servants were grumpy, we children were constantly being chastised, my father was irritated and even my mother was becoming increasingly anxious. Over it all presided Andrea; tall, thin, supercilious and constantly critical. Then, after some months of this, my grandmother arrived to stay. Andrea, though he would not have thought it when he first encountered this small, apparently insignificant woman, had met his match.

My grandmother’s visits were regarded with apprehension by all the household, except myself who unreservedly loved her. Days before her arrival Mboji and the rest would be scrubbing the kitchen from top to bottom and turning out the cupboards. Our kitchens were plain places then and not at all like the fancy “hostess” kitchens of today. Usually they were furnished with a large wooden table, a stainless steel sink and draining board, a white electric stove/oven with two round and one rectangular hot plates, a meat safe, a charcoal water-purifier on a stand, and a few dingy cupboards painted pale green or cream or possibly a combination of both. There would be a large pantry in one corner and a scullery near the back door. It was a room for preparing food, without pretension. No decor to speak of except a fly paper hanging from the ceiling, and a generally inadequate single-bulb light either naked or with a plain shade. This somewhat dreary part of the house was the cook’s fiefdom and memsaabs rarely ventured here. My grandmother, however, had an unusually un-memsaab-like preoccupation with hygiene, and was contemptuous of women who never set foot in their own chikoni. How else would you know whether it was being kept clean? How else prevent your family from being poisoned by germs? Our Kamba servants feared her but were accustomed to her ways; she lived near Machakos and spoke quite a bit of Kamba as well as functionally-fluent and often pungent kitchen Swahili, so during her first day or two with us there was always much warm Kamba greeting and exchanges about families and acquaintances back in the Ukumbani – Kenya could be a small country like that and servants that worked for you were often related to those working for members of your own extended family. Nonetheless, however hard our lot had worked to put the kitchen into tiptop shape, Memsaab Susu (as they called her – it means “witch”l) was never satisfied and it all had to be done over again until she was. My mother, considerably irritated by this bald attack on her housekeeping standards, kept well out of the way. Like most memsaabs we knew, she was content to leave her servants alone and not worry too much about what they did with their time, provided they were always there to tend the family as and when required. She liked a comfortable and aesthetically pleasing home but otherwise maintained a benevolent distance.

My grandmother, however, was different. When she’d done with our house she’d go and inspect the servants quarters and they, too, would have to be scrubbed down and disinfected. Servants’ children would be inspected for headlice and ringworm, stern lessons would be given on personal hygiene, hands would be inspected before preparing and serving food to ensure they had been properly washed with yellow Sunlight soap. The smell of Dettol and Jay’s Fluid was everywhere. Worse, my grandmother had an obsession with constipation; the state of our bowels was checked daily and all of us, servants included, were liberally dosed with Milk of Magnesia or Andrew’s Liver Salts.

Mboji and my grandmother had always enjoyed a wary (on his part) but amicable (on both parts) relationship. Though not a Kamba, he was a Taita, which she considered the next best thing. Andrea, however, she detested from the start, and it was reciprocated. Firstly, my grandmother did not appreciate his cooking, which was an insult to his pride so severe as to be almost mortal. For the first time we saw his self-esteem droop when she casually waved away his most tempting dishes. The truth was, though I don’t expect anyone bothered to tell him, that my grandmother rarely ate what my mother would have called “a normal meal”. She had a small appetite and preferred merely to nibble between meals, on cheese and biscuits, fruit, celery and pickles, anything that could be cut into small pieces and eaten anywhere but at the dining table.

When I look back, we ate a lot then, though we were all thin. Breakfast was always eggs cooked in one of several ways, with cereal and juice and toast as well. Kippers, too, when available. Mid-morning snacks were rare, but lunch was always a two-course meal, even if (when we were adults) we also had a full dinner in the evening. This meal was usually served no earlier than 8pm so between lunch and dinner we had afternoon tea at four o’clock, between work (or school) and whatever activities (usually sport) were planned for the late afternoon and evening. This “tea” always consisted of at least one kind of sandwich, biscuits and/or scones and a cake. Children had “supper” at about 6 – 7pm and this, too, was quite substantial; the something-on-toast already mentioned.

My grandmother didn’t bother with any of this, except on high days and special occasions, but stuck mainly to her cheese and bikkies, or the brown bread she bought specially in Nairobi. “I never eat,” she would say grandly and my mother would mutter something like “Well of course she doesn’t ever eat a proper meal, she’s always nibbling between meals.” Mboji used to make up little trays of things he knew my grandmother would like to pick at but often she would go into the kitchen and cut herself some cheese and take an apple from the ‘frig. This infuriated Andrea, who didn’t like memsaabs in his chikoni and had already suffered the indignity of having it cleaned, and himself along with it. For my grandmother was the type of Englishwoman who believed that only the English really understood cleanliness. And I mean the English, not the British, because though she might have accepted the Welsh (she was herself Welsh) and the Scots as practicing suitable standards she was very dubious about the Irish. She certainly had no high opinion of the French as a nation of clean-livers and any African trained by them must in her mind be in need of some strong instruction on the subject of both kitchen and personal hygiene. Domestic espionage was my grandmother’s forte and one day she caught Andrea not washing his hands before making his perfect pastry. Some pithy views were exchanged on both sides. And when my father came home for lunch that day, Andrea was waiting for him with his familiar: “Ah, bwana, shauri kidogo”.

This time he went too far. My father might often have found his mother-in-law irritating but he was not about to have her dissed by a servant. That would indeed have been letting the side down because though he was not a hard employer my father did expect both respect and obedience from those paid to serve us. So he very sharply put Andrea in his place and the latter, not over-endowed with humility, promptly resigned. A short while after he rather sullenly apologised and said he hadn’t meant it, but my father was not one to miss so good an opportunity and remained adamant. My mother was upset but not as much as the rest of us might have expected because even she was getting tired of Andrea’s tantrums and unfavourable comparisons of our household with others for whom he’d worked.

For a few days we had to put up with Mukiti’s efforts once more, and we ate out a lot, or fetched in fish and chips from Rocco’s or Chinese from the Hong Kong Restaurant. Then, in the mysterious way of Africans, Mboji arrived at the back door, asking for his old job back. To say our family was happy is to understate it. We were ecstatic! He must have been gratified by the warmth of our welcome. Of course, he fell off the wagon a few times after that and had to be bailed from gaol, but we put up with itfor the sake of his cheerful face and plain but honest food, and above all his roast chicken.

As I said at the beginning, my father maintained to his dying day that Mboji’s roast chicken was the best in all the world and for him no other, however wonderfully cooked, would do. Of course, he was quite wrong. I make a much better roast chicken than Mboji ever did, partly because I’m a better cook but mainly because chickens today, though perhaps not quite so tasty as those leggy, free range African kukus, are a lot more reliably tender and succulent.

And yet, like so many of my African memories, Mboji’s chicken has become sanctified by time and distance and, as with Proust’s little cake, one sniff of a chook roasting in my own oven and I’m back there in Kizingo Road waiting for our proudly smiling cook to bring his masterpiece to the table.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Mrs. R and the Tiger

Though Kenya is famous for its wild game the island of Mombasa has always been rather poorly equipped with wildlife, if you exclude marine creatures. Mongooses were plentiful, and birds and reptiles but no antelope or elephant or zebra and certainly no large feline predators.

Until, that is, the Day of the Leopard. Or, to be more correct, a couple of weeks of The Leopard because once, a long time ago, a rumour went racing round the island that a leopard had crossed from the mainland and was on the prowl. I can’t exactly remember the year but it was possibly 1959 or 1960, and I missed all the excitement because I was at boarding school in Nairobi.

Africans on their way home at night reported a large, spotted cat – a chui for sure, glimpsed slinking through gardens or following them at a discreet but still nerve-wracking distance. An Indian shopkeeper thought he saw the same creature skulking about when he was emptying some food bins one night. Soon sightings were coming from all parts of the island and these gained credence among the scoffers – such as my father – when pug marks were found in the grounds of the Church of England cathedral. The protestants of Mombasa considered this a definite triumph over the Papists down the other end of Fort Jesus Road and some wag suggested that the Provost of the Cathedral (not sure if it was still Rex Jupp at that time) buy himself a rifle! The pug marks were identified, by those who knew how, as being definitely those of a leopard.

After that the search was on, but the leopard proved elusive which, consider how crowded was our little island, without a lot of natural bush left upon it, is a tribute to the ability of big cats to conceal themselves from human view. We were not, in fact, particularly frightened of this particular big cat because leopards were not known to attack humans unless seriously provoked. However, a leopard is still a formidably strong and well-armed animal and who knew what it might do if it became hungry enough. Children were warned not to wander too far and dogs were kept indoors at night. As it was, any dogs that disappeared at that time were considered to have become leopard food and a couple of gung ho types actually sat up at night with native pi-dogs bought especially for the purpose and tied up as bait nearby, until the RSPCA put a stop to it. Men – European men at least – seemed to consider the whole thing a good joke but women and Africans – who were of course less-securely housed and more likely to be out on foot at night – were frightened. Indians were frightened too or at least the man behind the counter of our grocer, Beliram Parimal was, because, as he told us, “leopard is terrible man-eater”. In India, said my father, that’s quite true, for there leopard are larger than ours and also seem to be fiercer. He was a great fan of the books of the Indian hunter Jim Corbett, whose brother lived at Bamburi, and had not long since read The Man-eating Leopard of Rudraprayag. Unfortunately others in Mombasa had read this book too, borrowed from the British Council Library at Tudor, which probably helped fuel the general hysteria.

Leopard were, of course, quite common on the mainland wherever there was heavy forest. I myself saw them a few times – one on the roof of a cottage at Jadini Hotel, one crossing the road not far south of Malindi. When calves were taken at Kilifi Plantations a leopard was the suspected culprit and when I lived at Port Reitz my servants were afraid to walk home after dark because leopard were often seen in the vicinity. But a leopard on Mombasa Island would have to have either crossed the causeway, or Nyali Bridge, or swum across Tudor Creek or possibly the lower mangrove reaches of Kilindini Harbour. Suggestions that it might have crossed on the ferry from Likoni were generally disregarded! It all seemed so unlikely and even the reported pug prints in the church ground were regarded with suspicion by some – Mombasa was never short in those days of young practical jokers and some still remember the night a few of us drove all over Nyali pulling out name posts (remember those?) and swapping them around to confuse home owners and visitors. And then, suddenly, the leopard did something quite unexpected.

We lived in Kizingo Road and not far from us was a collection of small, cheap, thatched houses known collectively as “the bandas” and inhabited by the lower-ranking white local government employees. Among them was a woman I shall call simply “Mrs R”. She was married to a mechanic employed in the council workshops and her Lancashire origins were very obvious in an accent so broad that those of us who spoke “home counties” English could barely understand her – and thus she was much imitated behind her back. For Mrs R was not popular. She nagged her husband, gossiped spitefully about her neighbours, had few friends and was feared not only for her uncompromising opinions, loudly expressed in that harsh accent, but for her constant trouble-making. She was particularly unpopular with the neighbourhood children because, childless herself, she was always shouting at us to stay well clear of her house and garden and “keep roody noise daown”. I may be libelling the poor woman who has been dead many years now and thus unable to defend herself – but this is the way I (and others) remember her.

Mrs R was of that type and class – fortunately a tiny minority in Kenya – who went out to Africa purely for the job – and perhaps the sun – and appeared to get very little out of it. They never learned Swahili, never went into the bush or even a game park, never in fact stirred very far from their government-supplied house. They lived frugally in order to save to go “home” one day and buy a small bungalow at somewhere like Hove. They employed only one servant to do everything and as their houses usually contained little besides the basic PWD furniture this little was not much. In fact they feared and despised Africans and were, in turn, despised by those who did work for them and who preferred their bwanas and memsaabs to not interfere in the kitchen or lock up the pantry or dole out groceries with parsimony.

Mrs R was a case in point – she had a succession of servants from tribes who did not take well to domestic service and she treated them with rudeness and suspicion. Worse, she raised her voice to them in a way that other memsaabs would consider ill-bred as well as likely to be counter-productive. Possibly she did this because she had never bothered to learn any Swahili and believed, in true British fashion, that the only way to get a foreigner to understand you was to shout at them. Again, I am being rather harsh, and more than a teeny bit snobbish! But that’s the way it was. People like Mrs R never felt any kind of affinity with Africa, never felt the deep love felt by the rest of us, never tried to understand it, longed always for the day when she could finally return “home”. Where, no doubt, she would bore her friends and relatives with tales of her glory days as a memsaab. And people like Mrs R never took any interest in wildlife nor learned to tell one animal from another.

Ironic, therefore, that it was to Mrs R that the Mombasa leopard made its most famous appearance. According to two close neighbours, they were awakened late one night by a scream and a terrified voice calling out “Wilf, Wilf, it be taiger! It be taiger!”. When they rushed outside they realised the voice they were hearing was that of Mrs R, emanating from the conjugal bedroom. “Wilf, wake up!” she called. “It be taiger!”.

The way it was reported to me (and to many around the neighbourhood) Mrs R had been lying awake in bed when she saw a large, spotted, bewhiskered face peering right in her bedroom window. “When I realised what t’thing was,” she confided to my mother, “I were raight terrified”. Mrs R might not have known her animals but she did know a big cat when she saw one in her window, and had then woken up her sleeping husband. Loudly enough so that every one else in the neighbourhood (the bandas were very close together) could hear. The Story of Mrs R and the “taiger” winged its way round the island next day and she may well not have been believed except…that one of the neighbours who rushed to her aid reported later that his dog, an Alsatian known for its savage nature, had cowered whimpering at his side. And…the clincher…several pug marks of an unmistakable leopard nature were found in the soft sand of the garden bed outside Mr and Mrs R’s window.

The search was intensified but though expert trackers were brought in they found it difficult to find a trail through the little roads and gardens large and small that comprised the area between Kizingo Road, Prince Charles Street (as it was then) and Ras Serani Drive. However a couple of days later an African wandering under a baobab tree not far from the Likoni Ferry looked up and got the fright of his life, for there, draped nonchalantly over a branch, was the leopard. I got a fright too, when I heard about it, as did some of my friends, because this tree was a favourite play spot of ours and we’d even built a small cubby house in its thick, protective branches. The big cat was then captured, caged and (I think) released on the mainland. Nobody ever knew, conclusively, how it had got on the island, let alone why. The rumour mill ground out theories by the day – it had been brought on to the island deliberately as a joke; it was an escaped pet; it had escaped from one of Carr-Hartley’s zoo shipments at the port. The first might just possibly be true, albeit unlikely, the other two were obviously ridiculous because any escape would have been reported. And you don’t keep a large creature like a leopard in your home without friends and neighbours knowing about it…I’m just repeating this now to show how so many people don’t bother to think before they theorise!

We kids, of course, happily believed all the rumours in turn and even came up with a few of our own. One, I remember, was that the leopard (we always thought of it as “he”) would for sure have had a mate somewhere who would look for him everywhere and, through starvation and revenge, would prey on those who had taken him. Which shows that, back then, we knew little more about the habits of leopards than did poor Mrs R!

A Baobab tree, found all over eastern Kenya in the dry nyika country between the Nairobi uplands and the coast. Mombasa island was covered in them and legend had it that under each one was an Arab soldier, slain during the wars with the Portuguese who occupied Mombasa for a while. Baobabs are useful trees; the fruit is edible (though not particularly palatable) and a good substitute for cream-of-tartar, birds and other wildlife find refuge in the branches, some people even made temporary homes in them and we kids made cubby houses in them. We had a big specimen in our garden and I (with help from our gardener) made a snug little refuge there, impregnable to my ayah and most adults but not, alas, to my agile father!

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

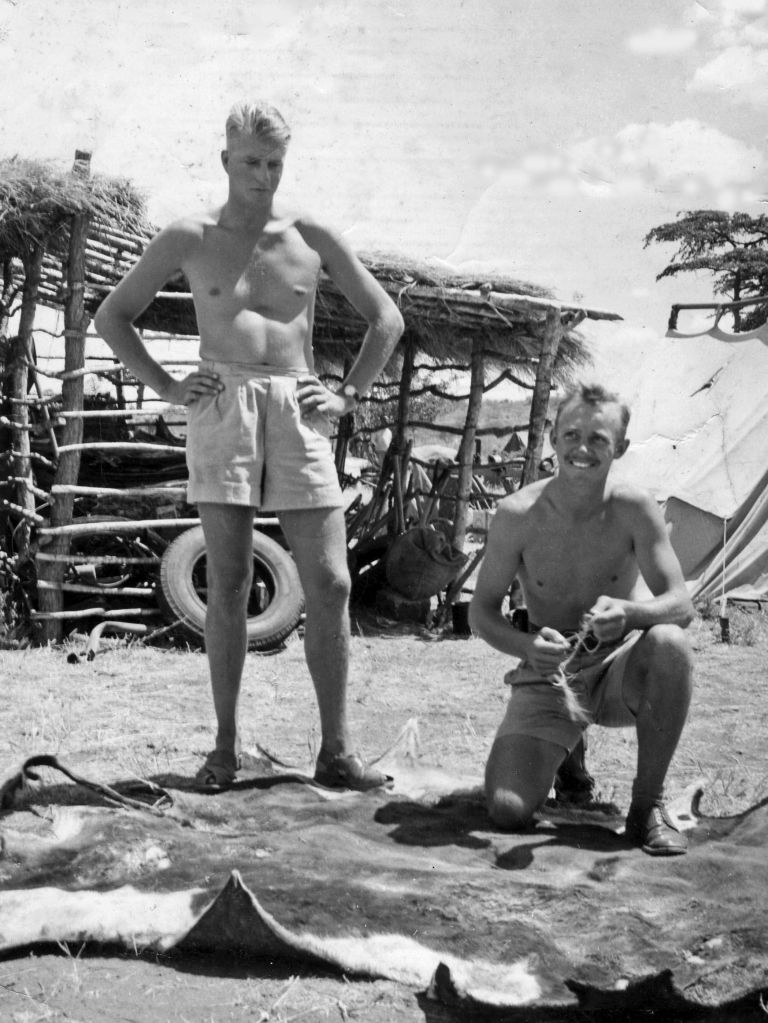

The great romance of travelling by train through the African bush

The world boasts many great train journeys. The Orient Express, the Trans-Siberian, the Rocky Mountaineer, South Africa’s Blue Train, Australia’s Ghan or Indian Pacific. I contend, however, that there have been few train journeys to rival the overnight trip between Mombasa and Nairobi in the years before 1963.

I’m going to try now and recreate that journey in my memory and because I was a Mombasa girl, and because the beginning of a journey is usually more exciting than the way home, it is always the “up” journey I remember, from the coast to Nairobi. Up-country types will, of course, remember it the other way around.

Travelling by train back then was more than just a journey, it was an Occasion. People dressed for it, casual but smart. No jeans or shorts for women and men planning to eat in the dining car had to wear long trousers and a tie. There was only one passenger train a day and it left at 6pm. It’s possible some travellers arrived at the last minute and flung themselves into their carriage just in time, enjoying none of the gracious ceremony of departure. But these would have been few and far between because most of us liked to arrive at the small but immaculate station in good time and, having checked out our compartment and found a porter to load our luggage, repair to the bar-cafeteria for a tea, a beer or a cocktail. You could buy a very good small plate of potato chips for next-to-nothing, I remember, or sandwiches and other snacks.

Leaving on the train was a social affair and the more people who came to see you off the more fun it was. Sitting there on the raised dais of the cafeteria you could survey your fellow passengers. There would be bashful honeymoon couples shedding confetti, businessmen in formal garb with briefcases, sun-reddened holidaymakers heading back home to Nairobi or Nakuru or even Kampala, smart young women on shopping trips to the superior retail outlets of the capital, men in safari suits, Indians in turbans or dhotis or vivid saris, perhaps a priest or two in dog collar and cassock, or a family of soberly-dressed missionaries. It was all very noisy and chaotic as people yelled greetings to acquaintances or farewells to those who came to see them off, and porters dodged in and out trying to get all the luggage safely stowed before departure, and station staff made occasional announcements over the tannoy which could barely be heard above the general din.

And, behind it all, the slow, steady, deep chuffing of a great engine getting up a head of steam. You were hardly aware of it at first, until it began to build to its crescendo of imminent departure and your pulse began to throb with it, excitement building along with the steam. You began to withdraw, a little, from those who had come to see you off and make common cause instead with your fellow passengers who, like you, were now moving purposefully towards the train that huffed and puffed like a great animal anxious to be on its way. You felt a sense of importance – The One Who Was Travelling, who was going places – and a sense of pity for those poor domestic creatures being left behind. A flurry of kisses, a hug or two, many more handshakes (for most of us were, after all, British!) and the usual banal injunctions “not to miss the train”. As if you would! Though inevitably there were one or two folk 1`frantically running and gesticulating and grabbing at door handles when the rest of the passengers were already safely aboard and taking up their positions at the windows, waving and grinning. Unless, of course, they had nobody to see them off, in which case they quietly took possession of their seats and took out their books, immune to the emotions of parting.

Then – the guard would blow his whistle and the last door would slam and there would be some flag waving from the boiler plate up front and the guard’s puny toot would be obliterated in memory by the thrilling shriek of the engine’s great steam whistle and all the romance of train journeys everywhere – from Dodge City to Bhowani Junction to the Coronation Scot – came together in one glorious moment as the pistons began their steadily-increasing rhythm and the mighty engine left the station, its many dull red carriages with their eager travellers following obediently behind. Oh, those mighty steam engines of my childhood! No wonder people still love them today; enough to collect them or buy books about them or gaze at them in museums. To us, they were neither quaint nor remarkable; merely the way we travelled. Yet we were not immune to their charm and power – even as a young woman I enjoyed going to look at the engine before departure and others did, too, with awe. When I was about ten, and not travelling myself but seeing somebody off, my dearest wish was realised when the engine driver invited me (and a couple of other kids) into his cab and showed us the controls and let us pretend we were driving the train. Everything in that cabin gleamed and shone with brass and rich wood. If only my father had been an engine driver and not a government official who went, dressed in tropical whites, to his dull old office every day. I would have much preferred him with dirty hands and a smut on his nose and a huge, powerful steam engine under his command!

In my memories those engines were either green and black or entirely black. I’ve been told there were also red ones but I never saw them. They always gleamed, their paintwork and brasswork immaculate, the letters “EAR & H” born proudly. Sometimes it took two of them – one at the back as well – to get the carriages up the two main scarps between the coastal strip and the plains of the Athi; I don’t know why this was; perhaps it was when the number of carriages exceeded the norm. Mostly, though, when there was still light in the sky, you could lean out the window and see, on a curving line, the fine sight of the engine up ahead, smoke pouring from its funnel (and putting smuts into your eyes if you weren’t careful!), pulling its line of carriages with apparent ease.